The Earl Raab Election(s)

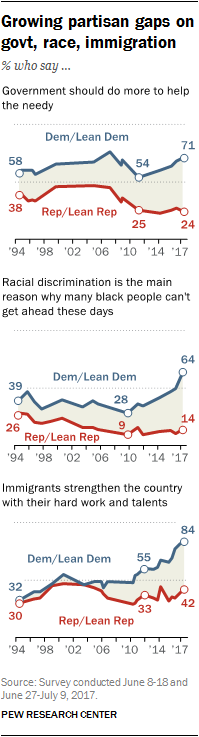

The Census Bureau has just reported that about half of the American population will soon be non-white or non-European. And they will all be American citizens. We have tipped beyond the point where a Nazi-Aryan party will be able to prevail in this country. We [i.e., Jews] have been nourishing the American climate of opposition to bigotry for about half a century. That climate has not yet been perfected, but the heterogeneous [i.e., multiracial] nature of our population tends to make it irreversible, and makes our constitutional constraints against bigotry more practical than ever.

Earl Raab, Jewish Bulletin of Northern California, February 19, 1993

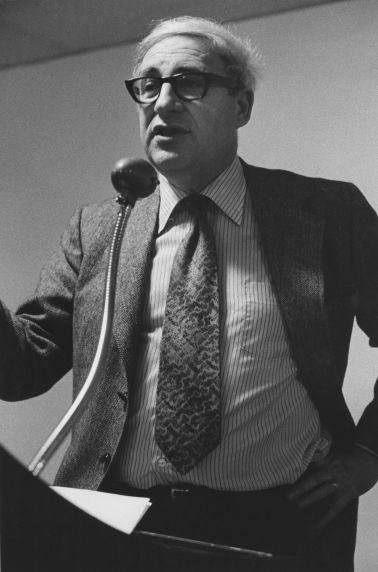

Earl Raab speaking at the 1972 AFT Los Angeles Civil Rights Conference

Note on usage: In this essay the racial designation “White” will be capitalized when used to mean racial Europeans and not capitalized (i.e., “white”) when conforming to common and official usage that includes non-European Caucasians (NECs) such as Middle Easterners and North Africans (MENAs) and semi-European Caucasians such as Ashkenazi Jews in the “white” racial category.

Earl Raab (1919—2015) served 40 years as the director of the Jewish Community Relations Council in San Francisco and was also the director of the Perlmutter Institute for Jewish Advocacy at Brandeis University. By “bigotry” and “Nazi-Aryan” in the above quotation, he means pro-White advocacy and support for White interests, the most existentially important of which are White preservation and independence — the continued existence of the White or European racial group and control of its own existence with its own countries, governments, cultures and economies. Earl Raab and his Jewish readership, the “we” in the above quote who are representative of the dominant and more active elements of the Jewish population, defined their group interests as diametrically opposed to White racial interests, promoting multiracialism, mass non-White immigration and racial intermixture, thereby causing White racial dispossession, subjugation, replacement and destruction. White interests, and especially the existentially important ones of continued racial life and independence through racial separation, are identified with and denounced as Nazism, racism, white supremacy, Fascism, etc. Thus even Donald Trump, whose perceived identification with implicit Whiteness is certainly far below any explicit support for existentially important interests, is frequently described as a racist, white supremacist, Nazi, etc., simply for opposing and obstructing, and so slowing, the progress of the anti-White agenda.

In 2016 the anti-White agenda of Raab, et al. was at the point of achieving Raab’s “irreversible” realization in a Hillary Clinton victory which would have swung the Damoclean sword and politically beheaded the White population, terminating its still remaining vestiges of political control of the country it created. They would do this by the legalization and enfranchisement of an estimated 22 million illegal non-White aliens (and possibly statehood for Puerto Rico and Washington D.C.), so that a party that served, promoted and defended White interests would no longer, in Raab’s words, “be able to prevail.”

But it was Donald Trump — the first major party presidential candidate in generations meaningfully identified with White interests, even if at a very low and implicit level — who won, not Clinton, and Raab’s triumphalism of 1993 suddenly seemed premature. Trump’s victory clearly demonstrated it was still possible for an implicitly pro-White candidate to prevail, and if so, also demonstrated the more remote possibility that a much more explicitly and meaningfully pro-White candidate and party could also still prevail.

So instead of realizing its complete and “irreversible” triumph over White America, the Anti-White Coalition suffered a defeat that shocked and shook it to its core. In response, it mobilized all the assets of its vast power structure to undermine the results of the election and make sure such a thing could never happen again. Before 2016 we could visualize the electoral future as a gradual racial transformation of the electorate to a non-White majority over the course of two or three decades in line with the projected demographic changes, but in the aftermath of Trump’s win it became clear that the Democrats planned to radically accelerate the racial electoral shift in their favor, plans postponed by Clinton’s defeat, but only until the next Democrat victory.

The approaching 2020 election — and if the Democrats lose this election, every election to come until the Democrats do win and impose permanent and “irreversible” non-White political dominance — will be as meaningful and decisive for America as the South African general election of 1994, which transferred political control of South Africa from the White minority to the non-white majority, was for the White population of that country. Every American election until the Democrats win will continue to be a sword of Damocles hanging over the neck of the White population which will finally fall when the Democrats win, striking off the White head (i.e., control or possession) of the country and imposing permanent non-White supremacy and the subjugation of Whites.

To realize the goal of White racial preservation and independence, the continued life of our race, and its control of its own existence, we must separate ourselves from the non-White races. To do this, it is necessary to be in control of the country, in fact very strongly in control, and to exercise that control with a firm and decisive will. To advance the same goal for our race in Europe, Canada and Australia we should so conduct ourselves in the process of separation that our racial kin in other countries will be moved to emulate our example rather than be repelled by it.

If our goal is to preserve as much of our race as we can, and if our goal of separation and independence for racial preservation is the goal consistent with the best interests of our race, then these goals would be best achieved by what Wilmot Robertson labeled the “National Premise,” a grand territorial partition of the country that would “spin off” the non-White racial populations into separate independent countries while keeping the greater part of the territory for a separate and independent all-White country. This separate and independent White country would contain the great majority of the White population (basically all who don’t self-emigrate to non-White areas) as well as the territory where the great majority of Whites reside, obliging less than 25% of them to relocate (the extent of White relocation should be minimized to maximize White support). This separate and independent White country would still be transcontinental and include the national capital and so be the continuation of the United States, and it would keep disturbance and disruption to a minimum (e.g., retirees would continue to receive their Social Security and Medicare benefits). I have previously discussed and described this goal in detail on this site in my essays “The National Premise Revisited” (with maps), my review of The White Nationalist Manifesto by Dr. Greg Johnson, and in two earlier articles in The Occidental Quarterly: “Visions of the Ethnostate” (vol. 18, no.3, Fall 2018 pp 29–46) and “Separate or Die” (vol. 8, no. 4, Winter 2008–2009 pp 15–38)

The most important measure of any separatist and preservationist proposal is what proportion of our race could it be reasonably expected to save, or is even designed to save. By such a measure the National Premise proposal for a grand or total separation is clearly the only sufficient preservationist solution. Such a solution is incomparably superior to the sundry much smaller-scale secessionist proposals that would have little or no lasting preservationist effect, making them no more than larger and more elaborate variants of White flight.

The National Premise goal can theoretically be achieved by different means, but by far the clearest and most structured path forward, and the one that would be least disruptive of people’s lives in every sense, would be within the existing political and electoral system established and long maintained by earlier generations of our race. This is the system to which the great majority of our people strongly adhere, regard as legitimate, and wish to continue.

We can conceive of this electoral path to White racial liberation and restoration (or instauration per Robertson’s more esoteric Latin term), as having multiple stages, and each stage having several steps (or hurdles). The first stage is the conversion or transformation of one of the two major political parties into a national populist party, and then over successive stages and steps into an implicitly and then explicitly pro-White party. Since the 1960s the Republican party has been the obvious vehicle for this development, but other than the steady migration of White voters to the GOP, no overt steps in a national populist direction were taken until Trump, whose election was the first official and historical step (one could say the first victory) for the national populist and ultimately pro-White movement. A basic outline of this electoral path would be:

Stage 1: The conversion or transformation of the Republican party into a national populist party. In many respects the policies of such a party would naturally tend to coincide with the interests of the majority element of the population, which in America, Europe, Canada and Australia would be Whites, including being restrictive of immigration, but it would seek to unify and integrate all parts of the citizenry and so be inclusive of the non-White elements, perhaps even pandering to them to address their complaints and attract their support. The efforts to restrict illegal immigration could include better border protection and enforcement (e.g., “the wall”), abolishing DACA and denying any form of amnesty for illegal immigrants, enacting mandatory E-Verify to restrict employment opportunities for illegals, denying government benefits and assistance for illegals, and possibly, assuming there is a strong enough popular mandate to provide the will, the forcible deportation of all illegal aliens.

Stage 2: The conversion of the GOP into an implicitly pro-White party. At the implicit level of the process pro-White policies would still be limited but would include greater priority and emphasis placed on combating illegal immigration with an increased determination to employ and enforce all the methods listed in Stage 1. Also at this stage there would no longer be any pandering to non-Whites, appeals to their special interests, or promotion of their inclusion and integration.

Stage 3: The further transformation of the GOP into a more actively, but still implicitly, pro-White party. This stage would include abolishing any programs or policies that overtly benefit or prioritize the interests of non-Whites, including Affirmative Action, “reverse discrimination,” or restrictions on rights of private association and discrimination, essentially repealing the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Stage 4: The continued conversion of the GOP into an explicitly pro-White party. At this stage of the process active measures would be supported to advance specifically White racial interests, but they would still be more defensive, ameliorative and temporary rather than decisive, complete and final. This would include means to secure White political dominance and efforts to promote various forms and degrees of racial separation.

Stage 5: The completed conversion of the GOP into an explicitly pro-White party. At this level of the process there would be open and determined advocacy for the complete and final, and only fully sufficient, solution to the issue of racial preservation and independence by the National Premise concept of a complete or grand racial separation through a grand partition of the country on racial lines.

The anti-Whites are very much aware of the threat such a development, made evident by Trump’s victory, poses for their previously unchallenged plans. The conversion of one of the major parties into a pro-White party, especially if it has enough White electoral support to win, is their worst political nightmare, and that is why they have mobilized all their power against it, with unprecedented and ferocious intensity, to “nip it in the bud” and abort the further development of a potential nascent pro-White movement. A second Trump victory would take the second step in Stage 1 even if only by consolidating the first step. A Trump defeat would probably set back the development of the GOP into a national populist, and increasingly more pro-White, party until it would be too late to matter.

How fast and far the Republican party can go in the process of its conversion over stages into an ever more pro-White party depends on the extent of its White support, and how fast and far its White support is willing to go. Trump won a very providential Electoral College victory in 2016 with 58% of the “white” vote, including 63% of white men and 53% of white women — the notorious “gender gap” celebrated by the anti-Whites. As the Jews and non-European Caucasians (NECs) commonly included in the “white” classification give most of their vote to the Democratic party (Jews consistently vote over 70% for Democrats) we can estimate that the GOP’s share of the White (European) vote is 2–3% greater than its share of the overall “white” vote, indicating that in 2016 Trump actually won 60–61% of the White vote. In the 2018 mid-term elections about 8 million Trump voters didn’t vote, and this decreased turnout for the GOP allowed the Democrats to take control of the House of Representatives with very adverse consequences, including the expected impeachment attempts.

When Trump began his candidacy in May 2015 he immediately jumped far ahead of his competition, with about 30% support in the polls of the Republican base, by emphasizing his opposition to illegal immigration and amnesty, including DACA, and promising to build a “wall” to stop illegals from crossing the southern border. This was and is a strongly pro-White position, although implicitly so, and beyond what any of his competitors were willing to match. He did not promise to deport the illegals who were already here, which would have been at the very limits of the parameters of acceptable political discourse, but his statements were enough to arouse the full fury of the dominant Anti-White Coalition far beyond anything or anyone since Nixon, and perhaps further than that. But his statements strongly opposing illegal immigration set off alarm bells among the anti-White establishment while also awakening the growing racial disquiet and concerns of a broad mass of Whites. These statements excited unprecedentedly enthusiastic support within the pro-White movement, with some seeming to think he could and would take the conversion process all the way through Stage 2.

Trump’s record on keeping his campaign promises is mixed, but not for lack of effort. He never seems to give up, and when blocked on one path, whether by congressional or judicial opposition, thinks out-of-the-box to find a way around to another path. His constituency is of course a coalition of somewhat disparate groups, although overwhelmingly White and to a large degree qualifying as populist. His most important constituency, in terms of numbers, is probably Evangelical Christians, and he has found it much easier to keep his campaign promises to them and other constituencies not related to racial or immigration issues than those that are related to race or immigration. Still he has tried, and stubbornly persists in trying to find a way. Despite congressional resistance and judicial obstruction. he has found creative ways to put together $18 billion to pay for about 1,000 miles of bollard fencing, the type of barrier preferred by the Border Patrol. As of mid-October, 341 miles of bollard fencing were completed and construction is continuing at a rate of about ten miles per week. About 500 miles is projected to be completed by the end of Trump’s first term. The remaining 500 miles of already funded fencing should be completed a year or so into his second term, assuming he has a second term. Otherwise the money will certainly not be used for further construction but might be used to tear down the fencing that has been built.

To Trump’s credit, on racial issues he has often gone beyond his campaign promises, taking bold action on matters not discussed in the campaign, which should be regarded as surprise bonuses by White advocates. Recently he denounced both “Critical Race Theory” and “The 1619 Project,” two of the leading current expressions of anti-White ideology, and banned the common practice of engaging in compulsory anti-White indoctrination sessions in the Executive branch and by government contractors, to the great discomfiture of professional anti-Whites like Tim Wise. On border enforcement he has pressured Mexico to allow apprehended illegal border crossers to be returned to Mexico to await the adjudication of their cases rather than being released into the U.S. where almost all of them disappear. He has also stopped the long practice of building federal housing projects—overwhelmingly populated by non-Whites—in primarily White suburbs.

To win the coming election without help from a second stroke of Providence or from an unlikely — and for us undesirable — major increase in his share of the non-White vote, and assuming the same voter turnout as in 2016, Trump will probably need to increase his share of the White (European) vote by at least several points to circa 63–65%, which would show in the tabulations as 61–62% of the overall “white” vote. To win the popular vote he would probably need to raise his numbers to at least 63% of the overall “white” vote, which could require as much as 66% of the White (European) vote. Assuming Trump does win, the larger the margin of his victory, and in particular the greater the extent to which his victory is attributable to White support, the stronger will be his mandate, the effects on the GOP and the spirit of his White supporters, creating a sense of confidence that will both enable and encourage bolder pro-White policies.

If Trump wins with a significant increase in White support it would also be another step in the process of transforming the GOP into a White people’s party, as an essential part of that process is decreasing the party’s dependence on non-White votes. Ideally, and ultimately necessarily as the party’s policies become more explicitly and meaningfully pro-White, the future White People’s party will need to be independent of non-White votes for electoral success, meaning it will need to win, based on the current 2020 racial proportions of the electorate, perhaps 80% of the White vote to win the popular vote, although the percentage required to win the electoral college, depending on the distribution of the votes, could theoretically be much less.

The other essential part of the process of converting the GOP into a White People’s party that is successful both electorally and in the actual implementation of pro-White policies is the continuation of a super-majority of White support as the party’s policies become more explicitly and meaningfully pro-White, ultimately to the point of a racial partition of the country to realize the “National Premise.”

This process of the conversion of the GOP into a White People’s party by steps and stages is at stake in the upcoming election. Trump’s election in 2016 was the first real step in the process. There is a common but misguided tendency for White advocates to focus too much on Trump in this election when our focus should really be on the process, the whole process, and nothing but the process. In this process Trump is only the first stepping-stone, or perhaps the first several stepping-stones depending on what happens, but the process is far bigger than him and hopefully will continue after he has left the scene. But that depends on whether he wins this election. Our choice is between a Trump victory that would likely mean the continuation of the process of transforming the GOP into a White People’s party, or a Democrat win that would be the “irreversible” Earl Raab election, essentially equivalent in effect to the 1994 general election in South Africa, reducing the founding White population to a state of racial dispossession and subjugation, and even persecution, leading ultimately to destruction.