“Modify the standards of the in-group”: On Jews and Mass Communications

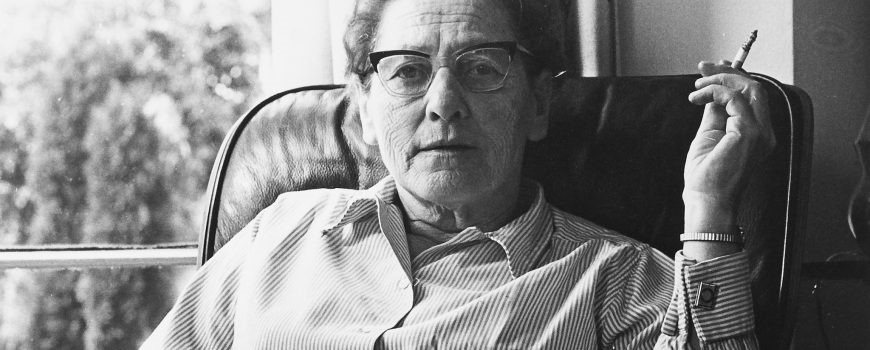

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in September, 2018, in two parts. It is a classic, and an important addition to the research on Jewish involvement in creating the culture of critique—the anti-White culture that we live in today. A revision to The Culture of Critique would of necessity include a summary and discussion of this material. The above photo is a testament to the way we live now—viewing the world through lenses shaped by activist Jews.

“To be successful, mass propaganda on the behalf of out-groups would have to modify the standards of the in-group.

Samuel H. Flowerman, Mass Propaganda in the War Against Bigotry, 1947.[1]

“The whole story is transparently barmy.” This is what Guardian journalist Jason Wilson had to say in a 2015 article discussing “conspiracy theories” about Cultural Marxism. Barmy, for the uninitiated, is a British informal adjective with the meanings “mad; crazy; extremely foolish.” Wilson continues by attempting to explain “the whole story”:

The vogue for the ideas of theorists like Herbert Marcuse and Theodor Adorno in the 1960s counterculture culminated with their acolytes’ occupation of the commanding heights of the most important cultural institutions, from universities to Hollywood studios. There, the conspiracy says, they promoted and even enforced ideas which were intended to destroy traditional Christian values and overthrow free enterprise: feminism, multiculturalism, gay rights and atheism. And this, apparently, is where political correctness came from. I promise you: this is what they really think … The theory of cultural Marxism is also blatantly antisemitic, drawing on the idea of Jews as a fifth column bringing down western civilisation from within, a racist trope that has a longer history than Marxism.

Re-reading this article recently, I wondered what Mr Wilson would say if I told him I possessed a document wherein an influential Jew linked to Marcuse and Adorno unambiguously sets out a scheme for the capture of the media, the mass brainwashing of White populations with multicultural propaganda, the manipulation of in-group culture to make it hostile to its own sense of ethnocentrism, the spreading of a culture of political correctness, and, ultimately, the co-option of the West by small ethnic clique pursuing its own interests under the guise of “promoting tolerance.” I wonder what he’d say if I told him the same Jew operated a network of hundreds, if not thousands, of other Jewish intellectuals engaged in the same single task — unlocking a psychological “backdoor” to White culture in order to completely reorient it. I think I’m correct in assuming that Mr Wilson would call me “barmy,” and accuse me of regurgitating the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. I suspect he would believe I’m a fantasist and an anti-Jewish conspiracy theorist. I know he’d dismiss even the possibility that such a document might actually exist. And yet it does exist.

The Intellectual Context

It’s quite possible that none of you have heard the name Samuel H. Flowerman, but I can say with certainty that you all, in a sense, know him nonetheless. If you’re even remotely familiar with the Frankfurt School, then you’re familiar with one aspect of his work. And, as we will soon discuss, if you find yourself living in a culture brainwashed into self-hatred then you’re familiar with another, though related, aspect of his work. Flowerman, it must be conceded, has been largely forgotten by history. He lurks in larger shadows left by “the exiles.” But Flowerman was in some respects as crucial a member of the Frankfurt School circle as any other. Of course, he wasn’t German-born. Nor was he a member of the Frankfurt School for Social Research. Instead, he was born in Manhattan in 1912, the grandson of a jeweler who arrived by ship from Warsaw’s Jewish district in 1885. And yet he would later achieve enough influence within his own group, as both activist and psychologist, to act as Research Director for the American Jewish Committee, and, most famously of all, to direct and co-edit the Studies in Prejudice series with Max Horkheimer.

For most who have in fact heard of him, this is perhaps the greatest extent of their knowledge of Flowerman. But for an accident, it would certainly represent the limits of mine. Very recently, however, I was conducting some research on Jewish activism in the cultural background preceding Brown v. Board of Education, and found myself, as I have so many times before, tumbling down the proverbial rabbit hole. After initially focusing on the figures of Jonathan Kozol and Horace Kallen (whose influence extends well beyond the popularisation of what he coined “cultural pluralism”), I came across a 2004 article in the Journal of American History by Howard University’s Daryl Scott titled “Postwar Pluralism, Brown v. Board of Education, and the Origins of Multicultural Education.”[2] Scott mentioned Flowerman because of the latter’s desire (pre-Brown) to inject theories derived from Studies in Prejudice into the education system, believing that moulding children was one of the best methods to achieve long-term and sustained socio-cultural change [see here for evidence the policy is continued to this day by the ADL].

Flowerman, a fan of post-Freudian psychoanalysis, possessed a background in both the study of education and of mass communication, and this heavily informed his thinking and activism.[3] In particular, he was doubtful that mass propaganda could, by itself, directly affect significant change among the White masses and make them abandon their “prejudice and latent authoritarianism” [i.e. acknowledging their own ethnic interests]. He was fascinated instead by the way peer group pressure exerted influence on the individual school children he had studied, along with the potential influence of teachers as shapers of minds as well as mere educators. For example, in a 1950 article for New York Times Magazine titled “Portrait of the Authoritarian Man,” Flowerman argued that, in order to produce “personalities less susceptible to authoritarian ideas, we must learn how to select better teachers and to train them better; we must see them as engineers of human relations instead of instructors of arithmetic and spelling.”[4]

The combined result of his research and thinking in these areas was his argument that it should be desirable for people like him to obtain control over the means of mass communication. Not only, argued Flowerman, should this control be used for blanket “pro-tolerance” propaganda, but it should also actively reshape in-group standards — thus reforming peer group pressures to become antagonistic to in-group ethnocentrism. His (then) highly ambitious goal was a culture that policed itself: a politically correct culture in which Whites, via peer pressure, conformed to new values — values much more user-friendly to Jews. His views and goals were later summarized by Herbert Greenberg, a colleague and co-ethnic in the same field, in 1957:

Flowerman de-emphasized the value and effectiveness of propaganda as a technique for reducing prejudice. He also agrees with the conception that techniques based on group structure and inter-personal relationships are the most effective.[5]

Flowerman and Greenberg were just two members of what was effectively a series of interlinked battalions of Jewish psychologists and sociologists operating with a kind of religious fervour in the fields of “prejudice studies,” opinion-shaping, and mass communications between the 1930s and 1950s, all with the goal of “unlocking” the White mind and opening it to “tolerance.” In a remarkable invasion (and creation) of disciplines similar to the Jewish flood into the medical and race sciences in the 1920s and 1930s, Jews also flooded, and then dominated, the fields of opinion research and mass communications — areas of research that overlapped so often under Jewish scholars like Flowerman that they were practically indistinguishable.

Even a quick review of lists of Past Presidents reveals that Jews were vastly over-represented in, if not dominated, the membership and presidencies of both the American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) and the World Association of Public Opinion Research (WAPOR). And of the four academics considered the “founding fathers” of mass communication research in America, two (Vienna-born Paul Lazarsfeld and Kurt Lewin) were Jews. Of the two European American founding fathers, most of Harold Lasswell’s graduate students were Jewish[6] (e.g., Daniel Lerner, Abraham Kaplan, Gabriel Almond, Morris Janowitz, and Nathan Leites) and he also sponsored the Institute for Social Research’s project on anti-Semitism.[7] The fourth, Carl Hoveland, had an equally Jewish coterie around him at Yale, where he operated a team of researchers along with Milton Rosenberg and Robert Abelson. Historian Hynek Jeřábek notes that Lazarsfeld’s influence in particular can’t be understated — by 1983, seven years after his death, “the directors of social research at the three largest media networks in the United States, CBS, ABC, and NBC were all his former students.”[8] Another Jew, Jay Blumler, has been called “a founding father of British media studies.”[9]

In fact, the Jewish dominance of the study of public opinion (and the potential for its manipulation) simply can’t be overstated. In addition to those already named, Joseph Klapper, Bernard Berelson, Fritz Heider, Leo Bogart, Elihu Katz, Marie Jahoda, Joseph Gittler, Morris Rosenberg, Ernest Dichter, Walter Weiss, Nathan Glazer, Bernard J. Fine, Bruno Bettelheim, Wallace Mandell, Hertha Hertzog, Dororthy Blumenstock, Stanley Schachter, David Caplovitz, Walter Lippmann, Sol Ginsburg, Harry Alpert, Leon Festinger, Michael Gurevitch, Edward Shils, Eugene Gaier, Joseph Goldsen, Julius Schreiber, Daniel Levinson, Herbert Blumer, I. M. A. Myers, Irving Janis, Miriam Reimann, Edward Sapir, Solomon Asch, and Gerald Wieder were just some of the hundreds of highly influential academics working in these fields that were born into Jewish families, associated heavily with other Jews, contributed work to Jewish organizations, married Jews, and yet concerned themselves with a degree of fanaticism with White opinion and ethnocentrism in America. This is to say nothing of their graduate students, who numbered in the thousands.

Despite some superficial differences in the titles of “opinion research,” “prejudice studies,” and “mass communications,” these academics all worked with each other to some degree, if not directly (in organisations or in co-written studies or papers) then via mutual associations. For example, it is a matter of historical fact that, in addition to three of the four founding fathers of mass communications research being Jews, all three were also very intimately involved with the Frankfurt School and the broader Jewish agenda to ‘adapt’ public opinion. Paul Lazarsfeld and Kurt Lewin, the two gurus of mass communication, together attended a 1944 conference on anti-Semitism organized by the research department of the American Jewish Committee (headed by Samuel H. Flowerman) and the Berkeley faction of the Frankfurt School in exile (headed by Theodor Adorno).[10] David Kettler and Gerhard Lauer also point out that Lazarsfeld was in regular communication with Max Horkheimer, was “strongly supportive of the Horkheimer Circle and its work,” and even furnished the latter with “notes and recommendations for the Horkheimer Circle’s unpublished ‘Anti-Semitism Among American Labor.’”[11] He was also a colleague at Columbia with and close confidante of, Leo Lowenthal.[12] By the late 1940s, Lazarsfeld’s ex-wife and mother of his child, Marie Jahoda, had even come to act as an American Jewish Committee liaison between Horkheimer and Samuel H. Flowerman, and co-wrote a number of articles on “prejudice” with Flowerman in Commentary.

One should by now begin to see clear connections forming between the American Jewish Committee, the Frankfurt School, “prejudice studies,” Jewish dominance of the academic field of “mass communications,” and, finally, the flow of influence from this field into the mass media (most clearly in the positions at CBS, ABC, and NBC quickly obtained by Lazarsfeld’s students). These connections will be important later.

A reasonable working hypothesis for such a sudden concentration of mutually networking Jews (often from different countries) in these areas of research would be that Jewish identity and Jewish interests played a significant part in their career choices, and that the trend was then accelerated by ethnic nepotism and promotion from within the group. Jeřábek appears to concur when he states that “Paul Lazarsfeld’s Jewish background, or the fact that many people around him in Vienna were Jewish, can help to explain his future affinities, friendships, or decisions.”[13] Setting aside the deep historical context of conflict between Jews and Europeans, a contingent and contemporary explanation might be that Jews were moved into fields involving mass opinion and perceptions of prejudice because they were deeply disturbed by the rise of National Socialism.

A more general, but, perhaps more convincing explanation considering their activities over time, is that these Jews were in fact disturbed by any form of ethnically defined and assertive White host culture. For example, some of the foreign-born academics listed above, such as Marie Jahoda and Ernest Dichter, had even been arrested and detained in pre-Anschluss, pre-National Socialist Vienna as cultural and political subversives in the early 1930s. They then made their way to the United States or the United Kingdom where they more or less continued the same behavior. It is highly likely that these individuals sought both to understand and change the mechanics of opinion and mass communications in their host populations in order to make it more amenable to Jewish interests. When they were effectively exiled from one host population they merely transplanted their ambitions to a new one. The only alternative hypothesis, long used in Jewish apologetics for any similar instance of Jewish over-representation, is that huge numbers of mutually networking Jews convened in these disciplines purely by accident. Nathan Cofnas and Jordan Peterson, for example, might argue that Jews accidentally entered these areas of study en masse simply because they possessed high IQs and liked living in cities.

The problem with such reasoning is that the work produced by these academics and activists was so highly focused against White American opinion, rather than appearing random or accidental, that it strongly indicates these scholars entered the field of mass communications with a clear and common agenda. For example, Jewish mass communications scholar Bernard Berelson was not just a researcher in public opinion, but also conducted a series of propaganda tests on how to make White Americans find their own ethnocentrism abhorrent. In 1945 he conducted a study in which a cartoon was shown to the public that made connections between Fascism and American culture. The cartoon, titled “The Ghosts Go West…,” showed ghosts leaving the graves of Hitler, Mussolini, and Goebbels, and flying to America carrying a banner that read: “Down with Labour Unions, Foreign Born, Jews, Catholics, Negroes.” The message was clearly that “intolerance” in America was basically the demonic ghost of fascism. Interestingly, however, the study found that Jews exposed to the cartoon were so fixated on the banner that they missed the underlying message altogether and believed the cartoon was a far right creation. The potentially confusing nature of the piece meant it was never deployed as a “pro-tolerance” propaganda weapon.[14]

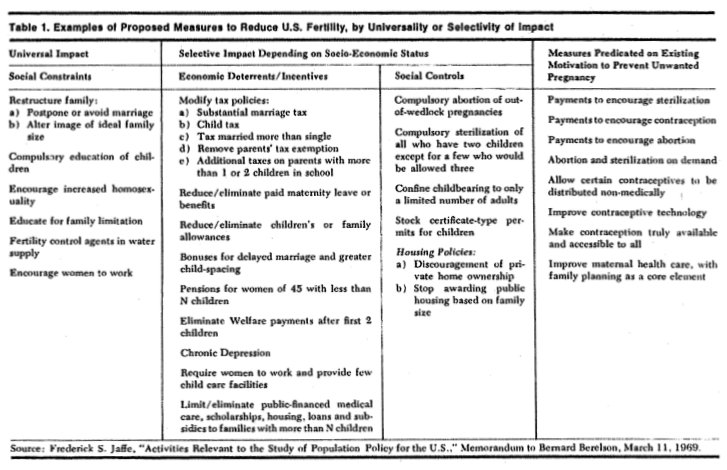

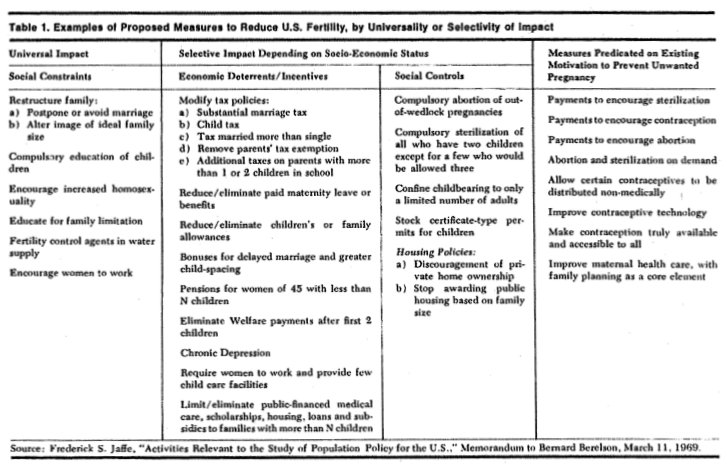

Berelson was also later a colleague and friend of Frederick S. Jaffe, the Jewish then-Vice President of Planned Parenthood. Both Jaffe and Berelson later became somewhat notorious because of a memo (known in history as the Jaffe Memo) sent in 1969 from the former to the latter, in which anti-White sociopath Jaffe put forth his own series of protocols that included a table that summarized many proposals from various sources regarding population control. This table contained proposals such as compulsory abortions for out-of-wedlock births, sterilizations for women with more than two children, encouraging homosexuality, and encouraging women to work. Both would also later work together on the infamous 1972 Rockefeller Commission Report which incorporated many of Jaffe’s proposals. We thus see more links between Jewishness, “prejudice studies,” the discipline of mass communications studies, and anti-White Jewish activism more generally.

In reality, the work of all these scholars orbited the same themes, if not openly, then more secretively (as in the case of Lazarsfeld’s work with the Institute for Social Research). Marie Jahoda, the ex-Austrian subversive, produced a series of studies that were mere variations on the theme of White ethnocentrism, something she pathologized most famously in Antisemitism and Emotional Disorder (1950).[15] In the same year, Morris Janowitz and Bruno Bettelheim worked together to produce Dynamics of Prejudice.[16] Meanwhile Joseph Gittler produced such works as “Measuring the Awareness of the Problem of Group Hostility,”[17] and “Man and His Prejudices.”[18] Herbert Blumer produced “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position.”[19] Fritz Heider worked with Kurt Lewin and Solomon Asch on unlocking the ways in which conformity could alter group behavior and individual opinions.[20] Ernest Dichter believed his studies of the mass communications in marketing could lead to the development of persuasive techniques that could “stop the new wave of anti-Semitism.”[21] The work of Walter Weiss concerned “mass communication, public opinion, and social change as they bear on changing racial attitudes.”[22] And aside from his secretive work with the Institute for Social Research, Paul Lazarsfeld, while working at the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University, introduced the notion of “social bookkeeping,” a systematic service that would note and evaluate “prejudice” in any material appearing in mass media of communications. I could go on.

Marie Jahoda

What we see here is the origins of an extensive Jewish joint enterprise in which the unlocking and alteration of White American public opinion is the goal. This is not conspiracy theory, but an established and provable fact. In a sense, the Frankfurt School, or Institute for Social Research, was the tip of an iceberg. The work of Horkheimer, Adorno et al, both drew from, and enthused, a large and growing army of Jewish academics working in the fields of public opinion and mass communications. This was a body of academics and activists keen to translate theories on “prejudice and the authoritarian personality” into action — to change the opinions and thinking of the host population. They would go on to develop forms of testing and analysis to further these goals, and their students would go on to take dominant positions in the fields of the mass media and mass communications. In many cases these academics speak openly of the need for control of the media and the mass dissemination of sophisticated propaganda (all of which could be tried and perfected at the expense of their universities in the name of ‘prejudice research’). Of all these activists, however, none produced a work more bluntly subversive than Samuel Flowerman’s 1947 essay “Mass Propaganda in the War on Bigotry.” It is to the protocols of Samuel H. Flowerman that we now turn our attention.

“Millions of leaflets, pamphlets, cartoons, comic books, articles — and more recently radio and movie scripts — have been produced and disseminated in the propaganda war.” Samuel H. Flowerman, Mass Propaganda in the War Against Bigotry, 1947.[1]

The Protocols of Samuel H. Flowerman

Samuel H. Flowerman, as Research Director at the American Jewish Committee, as colleague of the Institute for Social Research, and as a kind of hub for the expansive Jewish clique of mass communications scholars, was at the center of the drive to put Jewish “opinion research” initiatives into practical action. The clearest articulation of what this practical action would look like was articulated in his 1947 essay, “Mass Propaganda in the War Against Bigotry.” Flowerman’s foremost concern was that, although millions of dollars were being spent by organisations like the American Jewish Committee and the Anti-Defamation League on propaganda, propaganda may not by itself be sufficient for the mass transformation of values in the host population — in particular, for the weakening of its ethnocentrism.

Flowerman begins by explaining the format and extent of existing efforts: “Millions of leaflets, pamphlets, cartoons, comic books, articles — and more recently radio and movie scripts — have been produced and disseminated in the propaganda war (429).” Flowerman’s use of the language of warfare is of course interesting in itself and will be discussed further below. For now, we should focus on what Flowerman lists as the five aims of the “propaganda war”:

1. “The restructuring of the attitudes of prejudiced individuals, or at least their neutralization.”

2. “The restructuring of group values toward intolerance.”

3. “The reinforcement of attitudes of those already committed to a democratic ideology perhaps by creating an illusion of universality or victory.”

4. “The continued neutralisation of those whose attitudes are yet unstructured and who are deemed “safer” if they remain immune to symbols of bias.”

5. “Off-setting the counter-symbols of intolerance.” (429)

Flowerman concedes that the level of work and control required to achieve these aims would be extensive, and that the project was highly ambitious, seeking nothing less than “successful mass persuasion in the field of intergroup relations (429).” But he is equally clear in the conditions required for such success.

Flowerman’s first condition is “control by pro-tolerance groups or individuals of the channels of mass communication.” (430) Since Flowerman’s entire context of “pro-tolerance” activism was essentially Jewish, we may assume he is strongly implying that the channels of mass communication should fall into Jewish hands. Since “control” in Flowerman’s phrasing is not qualified, and since many newspapers, radio stations, and movie production companies were already in the hands of “pro-tolerance” Jews, the implication is also present that this control should be absolute. In addition, notes Flowerman, total control of these channels may still not be sufficient in itself. The host population will still need to be exposed to the productions of mass communications, and this was to be assured via “force, commercial monopoly, and/or crisis (designed or accidental).” (430) Only then would ‘pro-tolerance’ forces see “the persuasive devices and techniques of the elite playing upon the susceptibilities of the manipulated.” (430) Flowerman closes here with reference to Erich Fromm’s theory that people have “a desire

to be controlled.”

The second of Flowerman’s conditions for “successful mass persuasion in the field of intergroup relations” is saturation. This condition, like that of control and monopoly of the channels of mass communication, is intended as absolute. In other words, the message of “pro-tolerance” was to be ubiquitous and all-pervasive — beyond what was possible in 1947 and probably beyond what could even be conceptualized in 1947. In Flowerman’s words: “In addition to the large sums of money currently being expended on tolerance propaganda, significantly greater sums would probably be needed to achieve the degree of saturation — as yet hypothetical — required.” (430) The general idea here is to increase the “flow of pro-tolerance symbols” as a proportion of “the total stream of communications.”

In November 1946, a three-day convention, partly organized by Flowerman, was held in New York, bringing together “experts in the general field of public relations, including advertising, direct mail, film, radio, and press; professional workers on the staff of national and local agencies specifically concerned with fighting group discrimination; and social scientists from the universities and national defense agencies.”[2] Jews, of course, dominated all of these areas, and the list of attendees included the previously mentioned figures Bruno Bettelheim, Sol Ginsburg, Hertha Herzog (radio research director of McCann-Erickson, Inc.), Julius Schreiber, Paul Lazarsfeld, Joseph Goldsen, and Morris Janowitz. One of the findings of the mass communications scholars present at the convention was that even control and saturation may not be sufficient to ensure a transformation of opinions and values in the demographic majority. This was the case when the propaganda encountered particularly strong-minded individuals, or when the propaganda got lost in the overall stream of communications that one encounters in the course of everyday life. Flowerman thus writes with frustration that “we are developing a nation of individuals who work, worry, love, and play while news commentators, comedians, opera companies, symphony orchestras, and swing bands are broadcasting. This continuous onslaught for ‘something for everyone’ results in a kind of ‘radio deafness.’” (431) In order to overcome this obstacle, Flowerman returns to a key aspect of his first condition — the use of crisis (he writes that this can be “designed or accidental”) to focus attention on delivered propaganda. Flowerman writes:

As for overcoming the ‘radio deafness’ to commercial announcements and the general atmosphere of make-believe of radio entertainment, only symbols associated with acute crisis would seem to have a chance. For the great bulk of American people racial and religious intolerance is not regarded as a critical situation. … The absence of critical stress serves to diminish levels of attention to pro-tolerance symbols. (431)

Practical contemporary examples of what this tactic might look light would be the ubiquity of pro-diversity propaganda in the aftermath of Islamic attacks, Charlottesville, school shootings, moral panics about racism, ADL hype about the ever-present threat of anti-Semitism, murders by immigrants, and migrant drownings in the Mediterranean. The point here is that regardless of context, “crisis” is to be manufactured into almost every situation in order to focus attention on the real goal — the successful delivery of “pro-tolerance” messages, even (or especially) in circumstances in which tolerance has proven deadly, to the host population. Jews or, in the more ambiguous phrasing, “the agents of pro-tolerance,” would thus need to achieve (in Flowerman’s own words) the ambitious trifecta of “control, saturation, crisis.” (432) Crisis is therefore Flowerman’s third condition.

The fourth condition is the achievement of an alteration of predispositions in the individual via modification of their surroundings and peer pressure. Here Flowerman argues that “pro-tolerance” propaganda should not rely on intellectual means but instead on “social perception, which is affected by the predispositions of the audience. In turn, these dispositions are affect-laden attitudes which may have been produced by parents, teachers, playmates, etc.” (432)

The point here is that Flowerman and the mass communications clique believed that their propaganda would be better received by the masses if the psychological context of reception was itself changed. In other words, people raised in the demographic majority who are imbued with a sense of communal pride, social responsibility, cultural achievement, and national purpose are unlikely to be predisposed to be receptive to messages on behalf of outsiders. Some intervention in peer interactions and peer culture was thus necessary in order to break up such an obstacle to the reception of “pro-tolerance” propaganda. As just one example, we return here to Flowerman’s 1950 article for New York Times Magazine in which he argues for the training of teachers “as engineers of human relations instead of instructors of arithmetic and spelling.”[3] Children can thus “engineered” to be more receptive to “pro-tolerance” propaganda in adulthood.

This condition bleeds into the fifth — the manipulation of the basic instinct of humans to conform to group standards. Flowerman writes:

Consciously or unconsciously, individuals use group frames of reference in social situations even when they are physically separated from the group. … The strength of group sanctions is a potent force to reckon with even for an individual with a strong ego. … It would appear, then, that to be successful mass propaganda on behalf of out-groups would have to modify the standards of the in-group. … Mass pro-tolerance propaganda, to be successful, would have to change such values, which would be difficult to imagine without control, saturation, crisis, etc. (432)

What Flowerman is proposing here is essentially a revolution in values, after which a politically correct culture emerges where the demographic majority becomes self-policing and antagonistic to its own ethnic interests. In this environment — achieved via “control, saturation, crisis”— the strength of group sanctions among the White American in-group is directed towards manifestations of in-group ethnocentrism instead of outsiders. It’s nothing less than a proposal for the cultivation of White guilt and pathological altruism, and the diminishment of White ethnocentrism and cultural pride.

The sixth condition is the cultivation of influential figures on behalf of the “pro-tolerance” agenda. This required great subtlety. Flowerman writes that the research of his mass communications colleagues and co-ethics shows the targets of their propaganda:

are willing to assign to some individuals a stamp of approval which they deny to others … We know that many leaflets written and endorsed by popular heroes and accepted even by prejudiced individuals are often dismissed on the ground that they are being distributed by minority groups in their own self-interest. Many prejudiced individuals cannot conceive of such distribution by dominant groups. (433)

What Flowerman is here complaining of is the fact that some members of the demographic majority are perceptive enough to accurately point out the real origin of “pro-tolerance” propaganda, and to dismiss it on those grounds. By “minority groups,” the coy Mr Flowerman of course means Jews. He then cites a specific case:

In an experiment being conducted at the University of Chicago by Bettelheim, Shils, and Janowitz, veterans were exposed to pro-tolerance propaganda including a cartoon by Bill Mauldin. A prejudiced respondent, sharing the general esteem in which this popular soldier-cartoonist is held by ex-GI’s, said that he had regarded Mauldin as a “regular guy” but he supposed that if you paid a man enough you could get him to do anything; this respondent believed that the material he saw was being distributed by “a bunch of New York communists.” (433)

Thus we see the pathologisation of a veteran because he perceived with stunning accuracy the hand of subversion behind the use of a popular icon to promote an agenda entirely alien to his interests. Despite exceptions such as this veteran, the overall susceptibility of the masses was deemed sufficiently high for the strategy of “sponsorship” to be progressed. As a result, reports Flowerman,

propagandists, recognising the need for impeccable sources of authority, are producing material endorsed by popular heroes in sports, entertainment, and in the armed forces. Recently a plan has been developed to promote the insertion of full-page newspaper advertisements paid for and sponsored by “respectable” local business organizations. The effect of this campaign will have to be determined. (433)

Developed alongside his colleagues in the Institute for Social Research and the mass communications clique, these, then, are Flowerman’s six conditions for a radical transformation of values in the White American demographic majority:

1) Control of the channels of mass communications;

2) Saturation with Pro-tolerance messages;

3) Crisis, designed or accidental;

4) Diminishment of Cultural Pride and Self-esteem;

5) Cultivation of Self-Punishment and Group Self-Sanctioning;

6) Sponsorship of willing dupes or traitors.

Although these six conditions form most of the body of “Mass Propaganda in the War Against Bigotry,” Flowerman also spends some time discussing the ideal content of “pro-tolerance” propaganda. In this regard, he comments:

The most striking feature, the spearhead, of propaganda, is the slogan. … Current pro-tolerance or anti-intolerance slogans urge unity and amity, warn against being divided by differences of race and religion, describe our common origin as immigrants to these shores, remove myths about racial differences, and denounce bigots and bigotry. Some popular slogans are: Don’t be a Sucker!, Americans All —– Immigrants All, All Races and All Creeds Working Together etc.

Don’t Be A Sucker! was the name of a wartime film produced by the Army Signals Corps at a time when it was working heavily alongside Jewish Hollywood executives and script writers; its film production center was headed by Col. Emmanuel ‘Manny’ Cohen.[4] According to Wikipedia, the film:

has anti-racist and anti-fascist themes, and was made to educate viewers about prejudice and discrimination. The film was also made to make the case for the desegregation of the United States armed forces. An American who has been listening to a racist and bigoted rabble-rouser, who is preaching hate speech against ethnic and religious minorities and immigrants, is warned off by a naturalized Hungarian immigrant, possibly a Holocaust survivor or escapee, who explains to him how such rhetoric and demagogy allowed the Nazis to rise to power in Weimar Germany, and warns Americans not to fall for similar demagogy propagated by American racists and bigots. In August 2017 the short film went viral on the internet in the aftermath of the violent Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia and various copies have been uploaded to video sharing sites in the past year.

Flowerman was dissatisfied with the slogans of his time, however, believing them to be too “general in nature, vague as to goals, and unspecific as to methods.” (434) He believed that merely defining fascism as the enemy was insufficient because, at that time, the host population believed “fascism was strictly a foreign phenomenon characteristic particularly of Nazi Germany.” Propaganda depicting fascism as the enemy was therefore going to be ineffective in making the host population see its own values as oppositional and requiring destruction. Referring to works like The Authoritarian Personality, Flowerman writes: “Studies abound in which subjects subscribed to tenets of fascism although they rejected the fascist label itself. The pervasiveness of prejudice in so many individuals makes it difficult to set up a real enemy.” (434) He acknowledges that “in much anti-intolerance propaganda” the enemy is defined as “white, native-born Protestants,” but makes it clear that he wishes this to be expanded “for logical and psychological reasons.” One gets the impression that “Diversity is our Strength” and “Fight Hate” would have been much to his satisfaction.

*****

We now find ourselves returning to our point of departure. “The whole story is transparently barmy,” said the Guardian’s Jason Wilson when discussing “conspiracy theories” about Cultural Marxism. Consider again what he says this “conspiracy theory” amounts to:

The vogue for the ideas of theorists like Herbert Marcuse and Theodor Adorno in the 1960s counterculture culminated with their acolytes’ occupation of the commanding heights of the most important cultural institutions, from universities to Hollywood studios. There, the conspiracy says, they promoted and even enforced ideas which were intended to destroy traditional Christian values and overthrow free enterprise: feminism, multiculturalism, gay rights and atheism. And this, apparently, is where political correctness came from. I promise you: this is what they really think … The theory of cultural Marxism is also blatantly antisemitic, drawing on the idea of Jews as a fifth column bringing down western civilisation from within, a racist trope that has a longer history than Marxism.

In light of the facts addressed in this essay, such a theory would seem thoroughly borne out, with the only required alterations being that the process started before the 1960s and involved many more figures than the staff of the Institute for Social Research. The problem with people like Wilson is that they are proof of the very ‘conspiracy theory’ they refute. Raised in a controlled media, saturated with pro-tolerance propaganda, psychologically blasted with crisis after crisis, stripped of cultural pride, consumed by White guilt, and influenced by purchased “sponsors,” he is the perfectly gullible product of the protocols of Samuel H. Flowerman and the mass communications clique.

Not barmy, but more or less ridiculous, Wilson becomes an intellectual pygmy biting at the heels of his betters — those who, like the veteran in the study of Bettelheim, Shils, and Janowitz, see the true origin of the propaganda and are pathologized for their perceptivity.

[1] Flowerman, S. H., “Mass propaganda in the war against bigotry,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42(4), (1947) 429-439.

[2] S.H. Flowerman and M. Jahoda, “The study of man – can prejudice be fought scientifically?” Commentary, Dec., 1946.

[3] S. H. Flowerman, “Portrait of the Authoritarian Man,” New York Times Magazine, April 23 1950, 31.

[4] See for example, Richard Koszarski, “Subway Commandos: Hollywood Filmmakers at the Signal Corps Photographic Center,” Film History Vol. 14, No. 3/4, (2002), 296-315.

[1] Flowerman, S. H., “Mass propaganda in the war against bigotry,” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42(4), (1947) 429-439.

[2] D. M. Scott, “Postwar Pluralism, Brown v. Board of Education, and the Origins of Multicultural Education,” Journal of American History, Vol 91, No 1 (2004), 69–82.

[3] For an example of Flowerman’s thoughts on Freud and psychoanalysis see S. H. Flowerman, “Psychoanalytic Theory and Science,” American Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol. 8, No. 3, 415-441.

[4] S. H. Flowerman, “Portrait of the Authoritarian Man,” New York Times Magazine, April 23 1950, 31.

[5] Herbert Greenberg, “The Effects of Single-Session Education Techniques on Prejudice Attitudes,” The Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 31, No. 2 (1957), 82-86, 82.

[6] Ido Oren, Our Enemies and US: America’s Rivalries and the Making of Political Science, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, (2003), 13.

[7] Thomas Wheatland, The Frankfurt School in Exile (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 384.

[8] Hynek Jeřábek, Paul Lazarsfeld and the Origins of Communications Research, (New York: Routledge, 2017), 18.

[9] James Curran, “Jay Blumler: A Founding Father of British Media Studies,” in Stephen Coleman (ed) Can the media save democracy? Essays in honour of Jay G. Blumler (London: Palgrave, 2015).

[10] John P. Jackson and Nadine M. Weidman, Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press), 176.

[11] David Kettler and Gerhard Lauer, Exile, Science and Bildung: The Contested Legacies of German Emigre Intellectuals (New York: Palgrave, 2005), 184.

[12] James Schmidt, “The Eclipse of Reason and the End of the Frankfurt School in America,” New German Critique 100 (2007), 47-76, 47.

[13]Jeřábek, Paul Lazarsfeld and the Origins of Communications Research, 23.

[14] Bureau of Applied Social Research, “The Ghosts Go West”: A Study of Comprehension, (Unpublished), 1945, Directed by Bernard B. Berelson. Cited in Flowerman, S. H., “Mass propaganda in the war against bigotry,” 438.

[15] See for example, “The dynamic basis of anti-Semitic attitudes,” The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, Vol. 17, No. 2, (1948); “The evasion of propaganda: How prejudiced people respond to anti-prejudice propaganda” The Journal of Psychology, 23 (1947), 15-25; Studies in the scope and method of “The authoritarian personality. (New York, NY, US: Free Press, 1954); “Race relations in Public Housing,” Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 7, No. 1-2 (1951).

[16] Morris Janowitz and Bruno Bettelheim, Dynamics of Prejudice (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1950).

[17] Joseph Gittler, “Measuring the Awareness of the Problem of Group Hostility,” Social Forces, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Dec., 1955), 163-167.

[18] Joseph Gittler, ”Man and His Prejudices,” The Scientific Monthly, 69 (1949 ), 43-47.

[19] Herbert Blumer, ““Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position,” Pacific Sociological Review, 1 (Spring 1958), 3-7.

[20] Irvin Rock and Stephen Palmer, “The Legacy of Gestalt Psychology,” Scientific American, Dec 1990, 84-90, 89.

[21] Ernest Dichter, The Strategy of Desire (New York: Routledge, 2017), 15.

[22] Bert T. King and Elliott McGinnies, Attitudes, Conflict, and Social Change (New York: Academic Press, 1972), 124.

Marie Jahoda

Marie Jahoda