Vulture Capitalism, Jews — and Hollywood, Part 2

Go to Part 1.

The Big Short. Did things get any better in 2015 when the star-studded film The Big Short came out? Definitely not. Here we had Brad Pitt, Steve Carell, Christian Bale and Ryan Gosling — goys to a man — acting out the script of the book of the same name by best-selling author Michael Lewis (Moneyball, The Blind Side). And that script would be about how the subprime mortgage industry was slated for a big fall, with our main characters devising ways to place bets on such a fall. To them, there was a serious housing bubble and they meant to

collect when the collapse of the bubble came.

Ryan Gosling

This time, however, Hollywood alone cannot be faulted for seriously downplaying Jewish identity because gentile author Lewis already did that for them, thank you very much.

I had high hopes for Lewis’s book revolving around Jewish identity and was encouraged when I read the second sentence of Chapter One: “[Steve Eisman had] grown up in New York City, gone to yeshiva schools, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania magna cum laude, and then with honors from Harvard Law School.” Yes, I thought, this book was going to openly discuss Jewish identity on Wall Street.

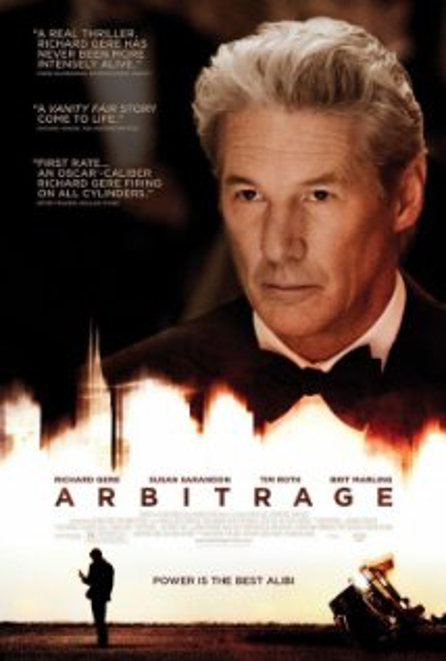

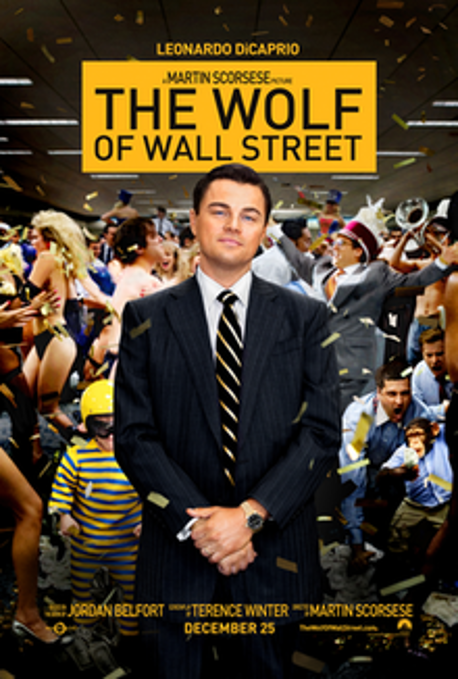

A few pages later, Lewis describes Eisman’s wife and her mother talking about the United Jewish Appeal, as well as how the young Eisman studied the Talmud to find its internal inconsistencies, so I thought we might have a Jewish tale on par with Jordan Belfort’s The Wolf of Wall Street. Alas, that was the last we heard of anything explicitly related to Jews or Jewishness. What a pity, since the subprime mortgage bond collapse was in fact an intensely Jewish affair.

We could have read about Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs, Maurice “Hank” Greenberg of AIG, Sandy Weill of Citigroup, Dick Fuld of bankrupt Lehman Brothers, or Alan Schwartz of the failed Bear Sterns—and many, many other Jewish players on Wall Street. Most remarkably, we read nary a word on the real powers in finance, people like those “The Three Apostles,” Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin or his successor Larry Summers. Nor do we read more than passing reference to two-term Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, who oversaw the entire life of the subprime mortgage fiasco, serving from 2006 to 2014.

Worse, we never read about the larger narrative surrounding the financial crisis of those years. (This review of then Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson’s account of the crisis gives a suitable feel for how tremendously dangerous the period was.)

In The Big Short, Lewis follows previously mentioned Steve Eisman, as well as a gentile California neurologist-turned hedge fund manager, Michael Burry. Also featured in the book is Greg Lippmann, head subprime manager at Deutsche Bank, but Lewis never once refers to Lippmann as Jewish. This just isn’t the story Lewis wants to tell, so it’s no surprise that Hollywood screenwriters also left out this important Jewish angle.

Turning now to the 2015 film version of The Big Short, we see that director and co-screenwriter Adam McKay, who is married to the Jewish Shira Piven, does, to his credit, faithfully show the scene where the young Eisman is in a synagogue with his rabbi. But my feeling is that this is done so much in passing that it will be lost on most gentile viewers. More to the point, however, is that actor Steve Carell simply doesn’t come across in any way as Jewish.

Steve Carell should have been Jewish

Now that we’ve looked at visual issues and identity in The Big Short, let’s consider some of the big dollar figures at stake. “Million” hardly has meaning in the debacle, with “billion” being a far more common term (and “trillion” popping up now and again). Despite the impression readers and viewers might have, the four main characters featured in book and movie were hardly the biggest players in the subprime mortgage game, though neurologist Michael Burry certainly did well, as this excerpt from a Vanity Fair article Lewis did in March 2010 shows:

It was precisely the moment he had told his investors, back in the summer of 2005, that they only needed to wait for. Crappy mortgages worth nearly $400 billion were resetting from their teaser rates to new, higher rates. By the end of July his marks were moving rapidly in his favor — and he was reading about the genius of people like John Paulson, who had come to the trade a year after he had. The Bloomberg News service ran an article about the few people who appeared to have seen the catastrophe coming. Only one worked as a bond trader inside a big Wall Street firm: a formerly obscure asset-backed-bond trader at Deutsche Bank named Greg Lippmann. The investor most conspicuously absent from the Bloomberg News article — one who had made $100 million for himself and $725 million for his investors — sat alone in his office, in Cupertino, California. By June 30, 2008, any investor who had stuck with Scion Capital from its beginning, on November 1, 2000, had a gain, after fees and expenses, of 489.34 percent. (The gross gain of the fund had been 726 percent.) Over the same period the S&P 500 returned just a bit more than 2 percent.

A far bigger winner was John Paulson, who appears briefly in the article, having spoken to Lewis for the book. Personally, what I’d like to have read about is Paulson’s bets on subprime mortgages. While Burry made just shy of a billion dollars, Paulson made history by earning $4 billion for himself in 2007, followed by $5 billion three years later. “Paulson, bucking the trends and the advice of other investors, gambled that the mortgage market would collapse. His bet paid off immensely. In 2007, the funds run by Paulson were up $15 billion — a staggering investment return rate of nearly 600%.” Of course, for career reasons, I can see why Lewis didn’t dwell on Paulson in the book, and naturally Hollywood was happy to let it go unmentioned.

Paulson’s mother was Jewish, and Paulson has worked in a highly Jewish milieu during his education and career, beginning with a Sidney Weinberg/Goldman Sachs scholarship. Later, he worked with Leon Levy at Odyssey Partners, then moved to Bear Stearns. His older sister, Theodora Bar-El, is an Israeli biologist. Perhaps I should read Gregory Zuckerman’s 2009 book The Greatest Trade Ever: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of How John Paulson Defied Wall Street and Made Financial History to fill in the missing gaps in this story. (And as far as I know, Hollywood has yet to make a film from Zuckerman’s book.)

Zooming out, we read in The Big Short that in total, according to an IMF estimation, about $1 trillion dollars was lost due to the subprime crisis. (Oddly, at the end of the film, we read: “When the dust settled from the collapse, 5 trillion dollars in pension money, real estate value, 401k, savings, and bonds had disappeared.” I can’t account for this large discrepancy.)

Let’s stick with the IMF’s estimate of $1 trillion. That’s a lot of billions in there, far, far more than Paulson’s money alone. So where did the money go? More to the point, who is responsible? Lewis allows his characters to blame stupid investment banks, but others point directly to those in charge of America’s finances: “The Three (Jewish) Apostles — Greenspan, Rubin, and Summers,” as well as Greenspan’s successor, Bernanke.

Time Magazine’s Entry in the “Most Ironic Story of the Year” Category

Just as when you throw a rock in the air at a Wall Street soiree you’ll almost certainly hit someone guilty, one can turn to practically any source on Greenspan et al.’s roles and find many suspicious characters. For instance, let’s consider this unlikely source for suspicion about what The Three Apostles and other high-placed Jews were up to — Clyde Prestowitz’s 2010 The Betrayal of American Prosperity. Here, Prestowitz notes how in 1989 and 1993, financial instruments that later played a central role in the meltdown of 2008–9 were exempted from government oversight. For instance, Greenspan was adamant about getting the government out of the way. “In fact, Greenspan largely halted the Fed’s active oversight of the banking industry.” Joined by Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and subsequent Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, “the three mounted an aggressive campaign to halt any efforts to regulate trading of new derivative instruments.”

When measures to impose constraints on these risky trades were being considered, Greenspan, Rubin, and Summers pointedly blocked them. Also, when Brooksley Born, Chairwoman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, attempted to do her job, Summers aggressively attacked her actions. Right on cue, Greenspan, Rubin and Arthur Levitt of the Securities and Exchange Commission pressured Congress to straightjacket Born. (I thought of the beleaguered Ms. Born when in the film version of The Big Short, Georgia Hale, an employee at Standard & Poor’s Financial Services, was grilled by a visiting Mark Baum [Steve Eisman].)

This bullying of Born persisted into 2000, as Greenspan continued to insist that Wall Street should be trusted and left to its own devices. “With those assurances, Congress went ahead and stripped the CFTC of responsibility for derivatives, and President Clinton signed the bill into law in December 2000.” Meanwhile, Ms. Born quietly left government service.

Money Monster. The last money movie I dissected was Money Monster (2016), starring two more big names: George Clooney and Julia Roberts. Clooney plays Lee Gates, the slick and jaded host of a TV financial advice show of the same name. Gates plugs a company which mysteriously loses $800 million, and many investors are ruined — including one who arrives at the studio and takes Gates hostage with an explosive vest.

The hostage taker is one Kyle Budwell (played by Anglo-Irish actor Jack O’Connell). Budwell is mentally challenged, as shown by his speech and childish behavior. For example, when his mother died and left him $60,000, he invested the whole amount in a company named IBIS, after Gates on a previous show highly recommended the stock. Budwell aims for revenge against Gates for his poor advice and against the CEO of IBIS, Walt Camby.

In the film people are busy behind the scenes finding out where corrupt CEO Camby is. It turns out that he made a secret trip to South Africa to advance his scheme to temporarily employ $800 million from his company to make a killing on a certain mining stock. The deal, unfortunately, falls through and the money is gone. This is then blamed on a “computer glitch” linked to sophisticated trading algorithms, but terrorist Budwell isn’t buying it. For that matter, Grant is becoming suspicious, as well as the head of PR at IBIS.

Emotions evolve. Even though enraged swindled invester Kyle Budwell has laced Grant with an explosive necklace, Grant has begun to feel growing sympathy for Budwell, and eventually we learn of another huge financial crime committed by the fictitious CEO Walt Camby. But of course, if you are going to have a financial criminal, he will have to be cast as not possibly Jewish. Wikipedia informs us that Dominic West, who plays CEO Camby, “was … the sixth of seven siblings … in a Roman Catholic family, largely of Irish descent.” So Jewish he ain’t.

Dominic West

Still, despite its obvious deception, Money Monster is instructive in a way. For those who understand which group is really culpable, a soliloquy by Budwell explains some of that group’s offenses:

I want everyone to know something. I might be the one with the gun here, but I’m not the real criminal. It’s people like these guys! [pointing to Grant and the set crew]. They’re stealing everything from us and they’re getting away with it, too. Nobody’s asking how. Nobody’s asking why.

You got to open your eyes out there. … the government’s no help. How they just look the other way, since after they’re done stealing our money, they barely even have to pay any taxes on it! I’m telling you, it’s rigged. The whole goddamn thing. They’re stealing the country out from under us. Not the Muslims. Not the Chinese. Them.

It’s all fixed. They like how the math adds up, so they got to keep rewriting the equation. Which means, the one time you finally get a little extra money, you try and be smart about it, you turn on the TV. Boom. That’s how they fucking take it. They take it so fast they don’t even have to explain it! They literally own the airwaves. They literally control the information.

That is very good: “Not the Muslims. Not the Chinese. Them.” Ah, yes. Budwell is blaming people like Grant, CEO Camby and those like them. But if you replace “they” and “them” with “Jews,” his speech is instructive indeed. Is it rigged? Well, anyone reading accounts of the trading patterns of Goldman Sachs, for one, will agree with that. Just Google it — you’ll get about 800,000 hits.

Also informative about Goldman Sachs is Budwell’s claim, “They take it so fast they don’t even have to explain it!” Many of us still remember the charges laid against Goldman in this respect. In brief:

While the SEC is busy investigating Goldman Sachs, it might want to look into another Goldman-dominated fraud: computerized front running using high-frequency trading programs. . . .

[Called] High Frequency Trading (HFT) or “black box trading,” automated program trading uses high-speed computers governed by complex algorithms (instructions to the computer) to analyze data and transact orders in massive quantities at very high speeds. Like the poker player peeking in a mirror to see his opponent’s cards, HFT allows the program trader to peek at major incoming orders and jump in front of them to skim profits off the top. And these large institutional orders are our money — our pension funds, mutual funds, and 401Ks.

Sort of like how the Kosher tax skims money off the food industry. I think what made the most pointed sense to me was Budwell’s linking of financial deceit with the power to create the (un)reality we see and hear: “They literally own the airwaves. They literally control the information.” This has been a key point others and I at TOO have made for years: Jews have immense media control throughout the West — and it’s killing us.

White societies throughout the world have been and continue to be subverted culturally, diluted through scandalous levels of non-White immigration, and drained of wealth and treasure, which Greg Johnson of Counter-Currents summed up so accurately:

Jews, of course, more than any other people, are aware of the necessary conditions of collective survival. They are concerned to secure these conditions for their own people even as they deny them to us. The obvious conclusion is that they mean for us not to survive as a people. America is being corrupted, exploited, degraded, and murdered by the organized Jewish community.

Johnson later added another idea relevant to my article here: “White Nationalism is an intellectual movement. We are a vast online educational project.” Indeed, TOO lives only on the Internet.

(I confess I was miffed when I read recently the following lines from Andrew Anglin in an otherwise good entry: “The grounds are fertile and the time has come for an open discussion about Jews in society. What we need now is an unironic, non-humorous take on the Jewish problem from serious people who are able to speak seriously about this serious problem.” Has TOO not been a leading source of serious discussion of this topic for two decades?)

Strike Through the Mask!

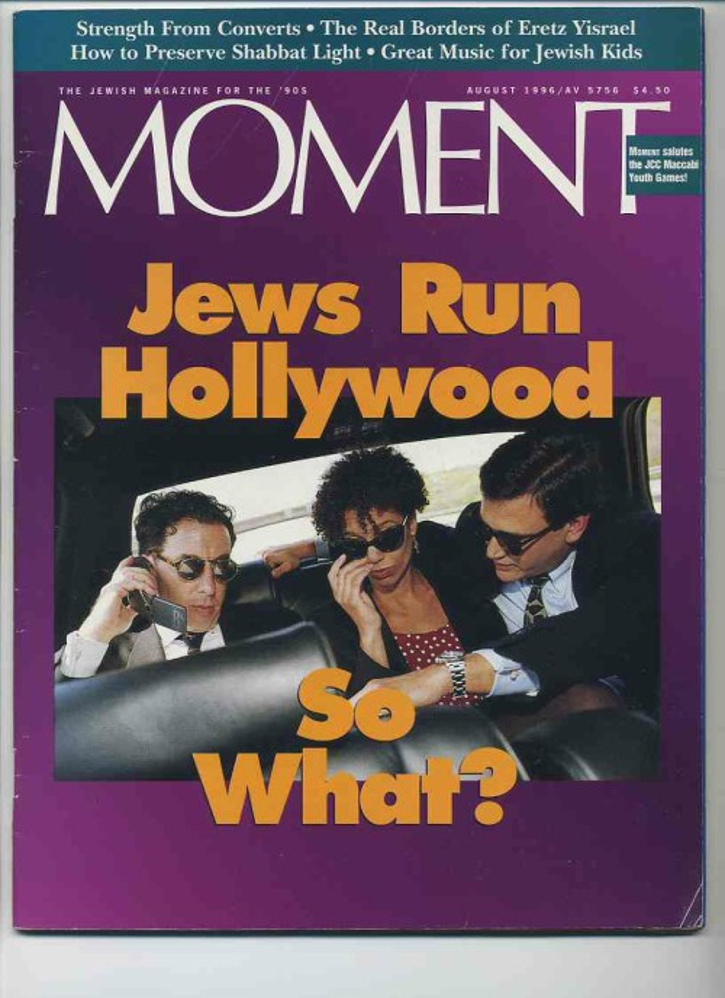

To recap, I’ll repeat the reasons for linking financial scandals with Hollywood: First, Jews run Hollywood. It is indeed an empire of their own. Second, Jews throughout modern history have been involved in immense financial scandals, reaching truly astonishing proportions in the last half century. Third, Jews use their Hollywood propaganda machine to obscure these facts. Case in point: This is the sixth major film I’ve featured that advances the deception about the Jewish role in financial skullduggery. As I’ve said, this is an explicit disinformation campaign.

Again plugging the recent TOO article from “Publius,” we see how the author has gone through volumes of evidence of interlocking Jewish financial and political activity. He then adds a nice literary touch when he quotes this, then expounds further:

“So you see, my dear Coningsby,” the Jewish Benjamin Disraeli wrote in his novel Coningsby, “that the world is governed by very different personages from what is imagined by those who are not behind the scenes.” It is my goal — and if I may be so bold as to speak for others, that of the other writers at the Occidental Observer and other dissident voices I’m sure — to shoulder our way into the conversation and show plainly the architects of this modern horror show. With any luck, figures like Steyer and Bloomberg will continue to drop the mask and show the public who they really are, making our job that much easier. To combat the pernicious agenda of the globalist establishment, we must first understand it. We must know the what’s, the when’s, the where’s, the who’s, the why’s, and the how’s and proceed accordingly. [emphasis added]

I’m glad Publius saw fit to mention the word mask, for that has been a driving theme of this essay. Joyce uses it by demanding that we “Strike through the mask!” and later explains how “these Jewish financiers also escape scrutiny by hiding behind the mask.”

I’ve tried desperately for years to help others see through this mask, in large part by examining the products Hollywood has inundated us with since the advent of moving pictures. My appeal to you is captured by Publius’s plea: “Do you see how all this works? This is how a decadent ruling class operates — governing for its own benefit and, for the preponderance of Jews, that of its tribe” [emphasis again added].

The half-dozen or so Hollywood films I’ve examined here at TOO play a central role in covering up what is so stunningly obvious. We need to understand these propaganda techniques and somehow teach others to see them as well. Otherwise, organized Jewry will continue to siphon off vast sums of money from the greater economy and employ it against the whole of the goyische world.

In closing, I’ll say that after “striking through the mask,” we must follow an observation from leading unmasker of Jewish behavior, E. Michael Jones, where he concludes a recent video with these simple but profound words: “Consciousness is the beginning of change.” MacDonald, Joyce, “Publius” — and, yes, Edmund Connelly — are doing everything humanly possible to “strike through the mask.”

I believe the present political crisis should be seen as a struggle between our new, Jewish-dominated elite, stemming from the 1880–1920 First Great Wave of immigration, and the traditional white Christian majority of America, significantly derived from pre-Revolutionary colonial stock but augmented by subsequent white Christian immigration. This new elite, while influential prior to World War II, had increasing influence throughout the 1950s—typically seen as a rather placid decade of peace and prosperity, but in reality, a decade of intense Kulturkampf roiling just below the surface but bursting out periodically, most spectacularly with the controversies surrounding Sen.

I believe the present political crisis should be seen as a struggle between our new, Jewish-dominated elite, stemming from the 1880–1920 First Great Wave of immigration, and the traditional white Christian majority of America, significantly derived from pre-Revolutionary colonial stock but augmented by subsequent white Christian immigration. This new elite, while influential prior to World War II, had increasing influence throughout the 1950s—typically seen as a rather placid decade of peace and prosperity, but in reality, a decade of intense Kulturkampf roiling just below the surface but bursting out periodically, most spectacularly with the controversies surrounding Sen.  Even more importantly, the Jewish community has been

Even more importantly, the Jewish community has been  As Peter Novick

As Peter Novick