Mark Potok, defendant

Glen Allen, an attorney from Baltimore, is doing what I wish I had been able to do a long time ago: sue the SPLC. His case is much stronger and much more sympathy-inducing than mine would have been. Basically, the SPLC got Allen fired from his job with the city of Baltimore where he was in charge of writing appeals in cases where Baltimore lost in the lower courts (“Lawsuit Claims SPLC Abetted Theft, Spread Lies to Destroy Lawyer for ‘Thought Crime’”). All it took was a simple phone call alleging that he has ideas that are unacceptable to the powers that be. In particular, he is accused of having supported William Pierce’s National Alliance in the past. As the notorious Heidi Beirich (a defendant in the case) stated in an interview, she “watched Allen ‘like a hawk’ because he had ‘the worst ideas ever created.'”

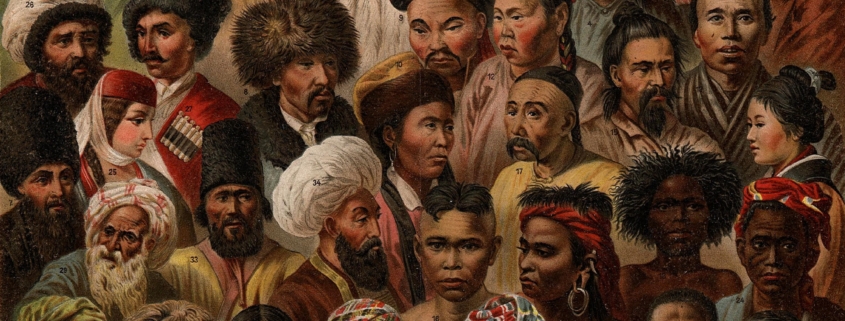

Presumably this refers to ideas like identifying with your racial or ethnic group and doing what one can to further its interests, as well as calling attention to groups that are antithetical to ideas of White identity and White interests. It goes without saying that such ideas are perfectly acceptable for every other racial and ethnic group in the U.S except Whites.

Allen’s complaint (here) is a brilliant, exhaustive account of the facts relevant to the case. I strongly recommend delving into it — it’s user friendly, even for a non-attorney. At the outset is a ringing defense of free speech and the First Amendment:

Providence has endowed humanity with the ability to grow and change. Indeed, we have a moral obligation to grow and change as we learn new aspects of reality. At the pinnacle of the means by which we grow and change should be robust dialogue, open debate, an aversion to taboos, and genuine conversation. This is the theory of our remarkable American traditions of free expression, as embodied, among other ways, in the First Amendment. But there are also other approaches to inevitable human discord. One is to draw lines of political or cultural orthodoxy, develop massive surveillance networks and extensive dossiers, and severely punish perceived transgressors who cross those lines, seem to cross them, or even seem to think about crossing them.

Beirich, Potok, and the SPLC, defendants in this case, have chosen this latter approach. Motivated by lucrative fundraising aims and employing fundraising techniques decried across the political spectrum as deceptive, the SPLC’s avowed goal, under the leadership of Beirich, Potok, and others, is to destroy, through public shaming, loss of employment, loss of reputation, and other severe harms, groups and persons the SPLC broadly defines as its political enemies.

Glen Allen, plaintiff in this case, is one of Beirich’s, Potok’s, and the SPLC’s victims. The cause of free expression itself is another, for the SPLC has become one of the most effective forces in the country for stifling honest and robust debate on controversial issues. Beirich, Potok, and the SPLC are entitled to espouse their outlook forcefully. They are not entitled, however, to the following actions, all alleged and supported in this complaint: to receive, pay for, and use stolen documents, including confidential documents and documents protected by attorney client privilege, to tortiously interfere with Allen’s prospective advantage in employment; to defame him by publishing false statements that he was “infiltrating” the City of Baltimore’s Law Department; or to masquerade as a 501c3 public interest law firm dedicated to a tax exempt educational mission, when in reality the SPLC fails the basic requirements for this favored status because of its illegal actions (including numerous instances of mail and wire fraud), multiple violations of canons of professional ethics (including improper disclosure of confidential and privileged documents and failure to train its nonlawyer employees), orchestration of violations of the constitutional rights of the organizations and individuals it targets, and sensationalist supermarket tabloid style one-sided depictions of its victims.

The reality is that Beirich, Potok, and the SPLC have perfected what the scholar Laird Wilcox, speaking of the SPLC, called “ritual defamation”: “a way of harming and isolating people by denying their humanity and trying to convert them into something that deserves to be hated and eliminated. They accuse others of this but utilize their enormous resources to practice it on a mass scale themselves.

Beirich, Potok, et al. don’t even pretend to engage in honest debate and the free flow of ideas. Atty. Allen quotes Potok: “We see this [as a] political struggle, right? … I mean, we’re not trying to change anybody’s mind. We’re trying to wreck the groups, and we are very clear in our head, … we are trying to destroy them.” And in this case, the attempt to destroy Allen goes far beyond ethical and legal norms — not surprising given the SPLC’a sordid history of using smear tactics and hypocrisy (Section 31) as well as their dedication to fund-raising far beyond what they actually use to further their causes (Section 27).

Of course the attempt “to destroy” people and groups with ideas they don’t like has now spread far beyond the SPLC, including financial firms refusing credit card services, de-platforming on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, and banning from crowd-funding sites like Patreon. As noted here several times, TOQ and TOO have been subjected to these forms of de-platforming.

At present there is an ever-escalating war against the dissident right. This war is not based on developing clearly articulated arguments designed to persuade reasonable, intelligent people. Instead, our new elite rely on wall-to-wall propaganda spread throughout the media and educational system — propaganda designed to make the traditional White majority accept its fate as a declining, soon-to-be impotent minority. Our new elite is terrified that White people be exposed to these ideas. Terrified that they will stop being ashamed to proudly identify as White and do what they can to prevent a the impending disaster to White America. They are terrified because they realize that, beneath all the propaganda raining down from the media and the educational system, the emperor has no clothes — pseudoscience like: there is no biological basis for racial classifications, no biologically based race differences, and no intellectual basis for Whites having legitimate interests in creating a safe and prosperous future for themselves and their progeny. Read more