Toward the Future We Have Yet to Shape: A Review of Mjolnir 4: The Wedding March

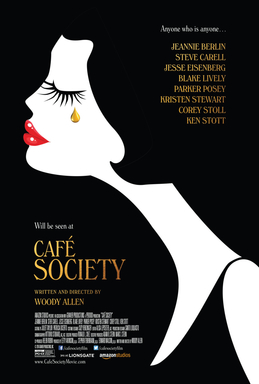

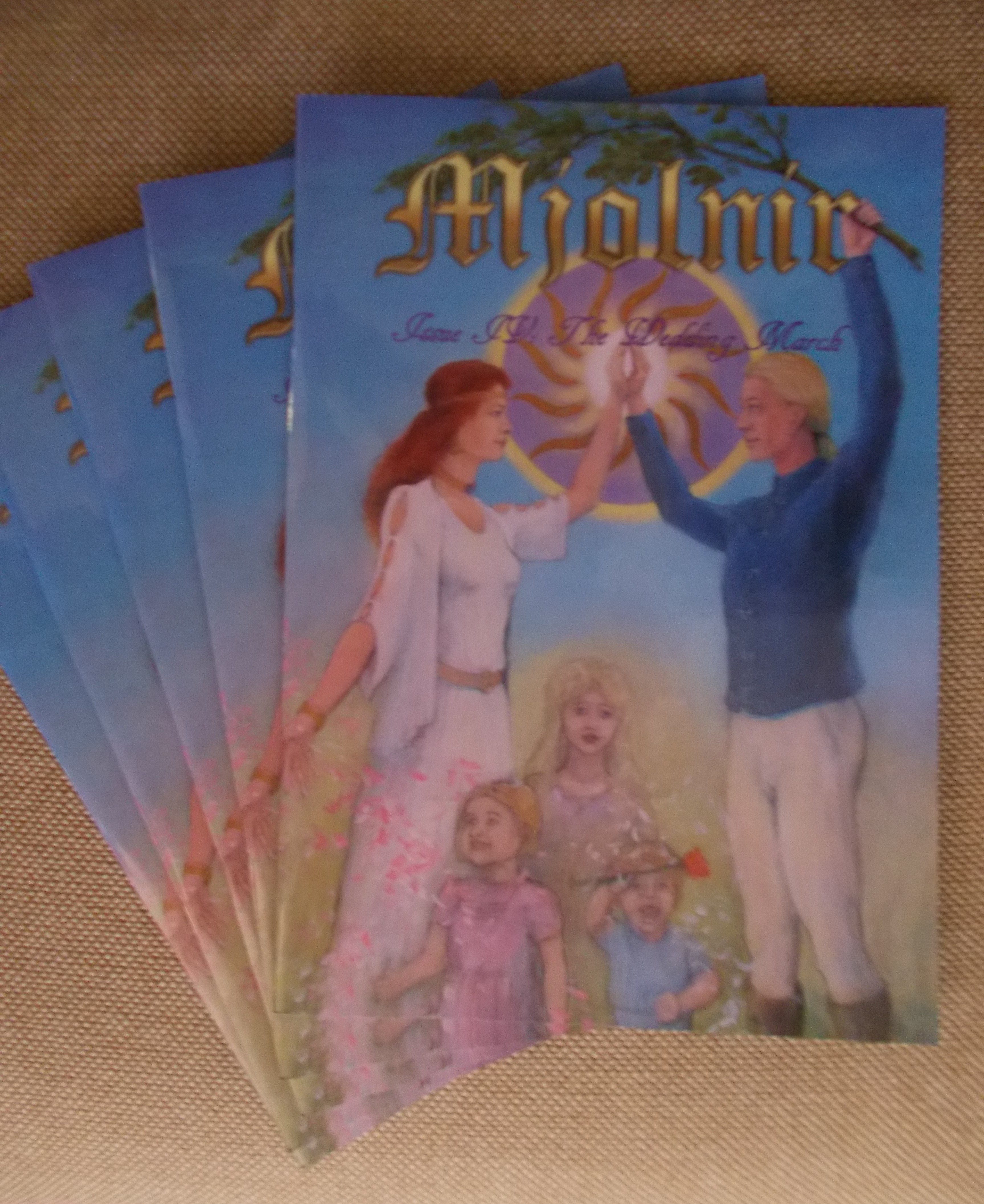

Mjolnir 4: The Wedding March

So many magazines become formulaic by Issue 3, let alone Issue 4. Mjolnir Issue 4 –subtitled “The Wedding March”—is not one of them. Mjolnir never has been. It is always a delight to receive the latest copy, not knowing what interesting words and pictures wait inside those full color glossy covers.

Not to say that Mjolnir is chaotic or haphazard—far from it. Editor Dave Yorkshire does a splendid job of keeping to his original statement of intent: to publish true Eurocentric traditional art forms, and he has managed to do it for four issues so far, remaining elitist and illiberal in the best possible manner. (I see in his editorial that he is testing the waters of YouTube via the Alt-Right channel Millennial Woes, and also checking out the feasibility of holding regular Eurocentric Cultural Festivals—both of which I am sure Mjolnir will successfully navigate in due time).

The essence of “The Wedding March” is summed up nicely in the final sentence of the editorial: “If European Man is to survive, he must embrace a future that is vernal rather than autumnal, that promotes life, birth and rebirth, and marriage as the sacred pact that binds this continuum that stretches from the prehistoric past into the future we have yet to shape.”

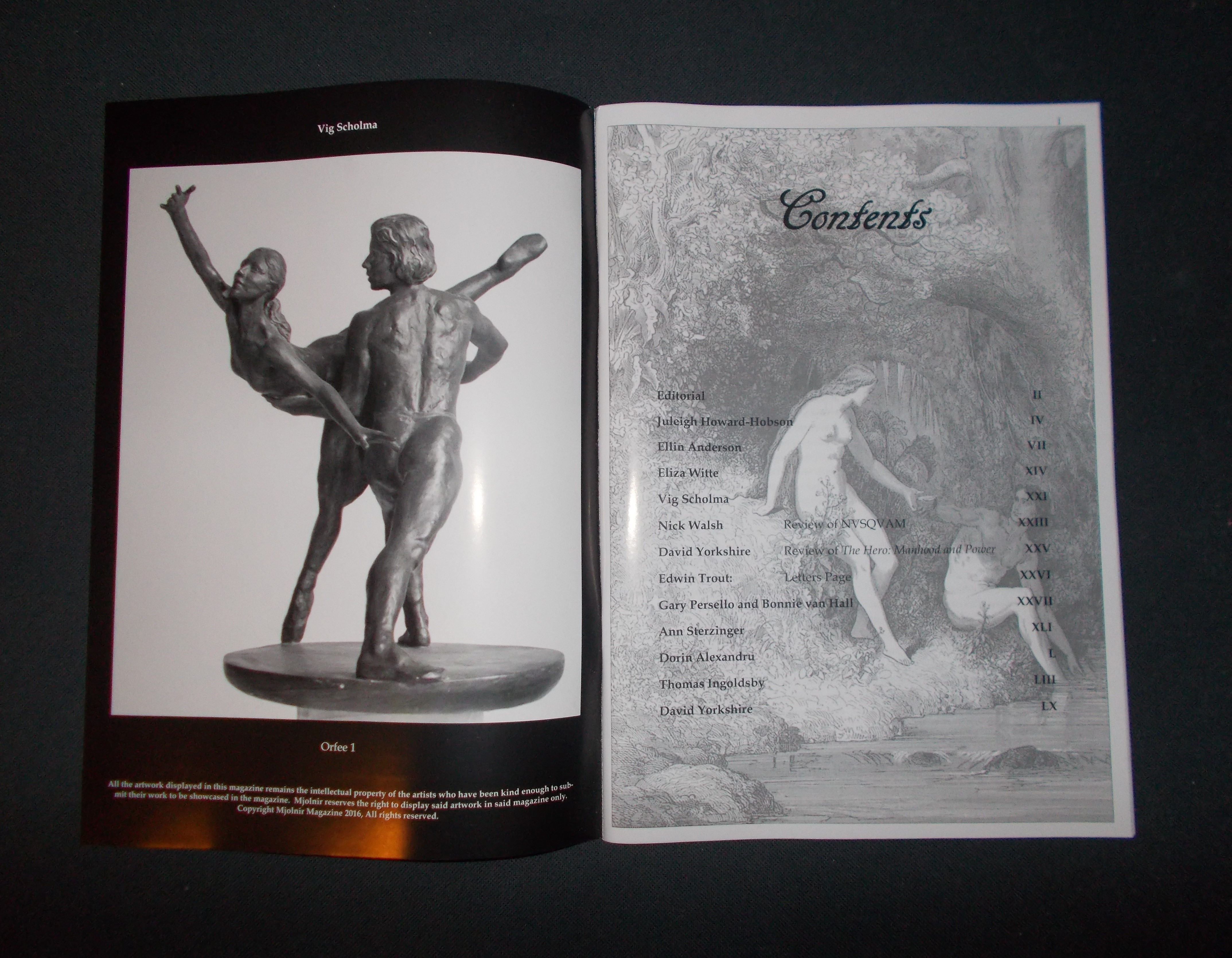

We’ll skip over my contributions to this issue, only noting that I contributed poetry as well as a short story, and turn first to the literary contributions of others. And there are many to savor, from all areas of the European literary triad: fiction, drama and poetics. Contemporary poets Ellin Anderson, Eliza Witte and Dorin Alexandru; nineteenth-century narrative poet Thomas Ingoldsby (pen name of Richard Banharm, in case you wanted to know), fiction writer Ann Sterzinger, and Dave Yorkshire himself with another ultimate gem in the form of a parody/drama.

Contents and sculpture by Vig Scholma

It is customary during the annual Hajj pilgrimage that Muslim devouts throw pebbles at three walls (formerly pillars), called jamarāt, in the city of Mina just east of Mecca. One of a series of ritual acts that must be performed in the Hajj, it is a symbolic re-enactment of Abraham’s hajj, where he stoned three pillars representing the temptation to disobey God and preserve Ishmael. The ceremony is commonly known as “the stoning of the Devil,” and may be regarded as a practice designed to reinforce socio-religious conformity and obedience.

It is customary during the annual Hajj pilgrimage that Muslim devouts throw pebbles at three walls (formerly pillars), called jamarāt, in the city of Mina just east of Mecca. One of a series of ritual acts that must be performed in the Hajj, it is a symbolic re-enactment of Abraham’s hajj, where he stoned three pillars representing the temptation to disobey God and preserve Ishmael. The ceremony is commonly known as “the stoning of the Devil,” and may be regarded as a practice designed to reinforce socio-religious conformity and obedience.