Tristan Tzara and the Jewish Roots of Dada, Part 3

Dada in New York

According to Marcel Duchamp’s own account, in late 1916 or early 1917 he and Francis Picabia received a book sent by an unknown author, one Tristan Tzara. The book was called The First Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine and had just been published in Zurich. In this work Tzara declared Dada to be “irrevocably opposed to all accepted ideas promoted by the ‘zoo’ of art and literature, whose hallowed walls of tradition he wanted to adorn with multicolored shit.”[i] Duchamp later said: “We were intrigued but I didn’t know who Dada was, or even that the word existed.”[ii] Tzara’s scatological message was the catalyst for the establishment of the antipatriotic and anti-rationalist Dada message in New York, and it may well have informed Duchamp’s decision to submit his infamous Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

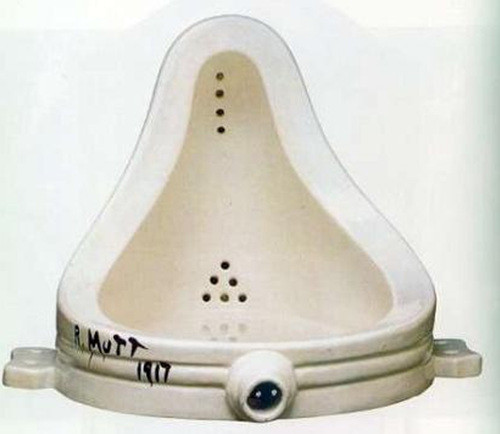

In February 1917 Duchamp famously sent the Independent an upside-down urinal entitled Fountain, signing it R. Mutt (famously photographed by Alfred Stieglitz). By doing so Duchamp directed attention away from the work of art as a material object, and instead presented it as something which was an idea. In doing so he shifted the emphasis from making to thinking.

Duchamp later did the same with a bottle rack and other items. Through subversive gestures like these he parodied the Futurist machine aesthetic by exhibiting untreated objets trouvés or readymade objects. To his great surprise these became accepted by the mainstream art world. Read more