The AEI, a Major Neocon Thinktank, Implicated in the Sackler Family’s Opioid Crisis

My 2017 article on the Sackler family and the unfolding opioid disaster (“Opioids and the Crisis of the White Working Class”) emphasized the corruption of the academic and medical establishment:

As in The Culture of Critique, this was a top-down movement based ultimately on fake science created at the highest levels of the academic medical establishment, motivated by payoffs to a whole host of people ranging from the highest levels of the academic-medical establishment down to sales reps and general practitioner physicians.

Now Tucker Carlson has uncovered another angle intimately tied to our new Jewish elite: the American Enterprise Institute (AEI). The AEI figured prominently in my article “Neoconservatism as a Jewish Movement,” published in 2004:

Jewish intellectual and political movements also have typically had ready access to prestigious mainstream media outlets, and this is certainly true for the neocons. Most notable are the Wall Street Journal, Commentary, The Public Interest, Basic Books (book publishing), and the media empires of Conrad Black and Rupert Murdoch. Murdoch owns the Fox News Channel and the New York Post, and is the main source of funding for Bill Kristol’s Weekly Standard—all major neocon outlets.

A good example illustrating these connections is Richard Perle. Perle is listed as a Resident Fellow of the AEI, and he is on the boards of directors of the Jerusalem Post and the Hollinger Corporation, a media company controlled by Conrad Black. Hollinger owns major media properties in the US (Chicago Sun-Times), England (the Daily Telegraph), Israel (Jerusalem Post), and Canada (the National Post; fifty percent ownership with CanWest Global Communications, which is controlled by Israel Asper and his family; CanWest has aggressively clamped down on its journalists for any deviation from its strong pro-Israel editorial policies. Hollinger also owns dozens of smaller publications in the US, Canada, and England. All of these media outlets reflect the vigorously pro-Israel stance espoused by Perle. Perle has written op-ed columns for Hollinger newspapers as well as for the New York Times.

Neoconservatives such as Jonah Goldberg and David Frum also have a very large influence on National Review, formerly a bastion of traditional conservative thought in the US. Neocon think tanks such as the AEI have a great deal of cross-membership with Jewish activist organizations such as AIPAC, the main pro-Israel lobbying organization in Washington, and the Washington Institute for Near East Policy [which produces pro-Israel propaganda]. (When President George W. Bush addressed the AEI on Iraq policy, the event was fittingly held in the Albert Wohlstetter Conference Center.) A major goal of the AEI is to maintain a high profile as pundits in the mainstream media. A short list would include AEI fellow Michael Ledeen, who is extreme even among the neocons in his lust for war against all Muslim countries in the Middle East, is “resident scholar in the Freedom Chair at the AEI,” writes op-ed articles for The Scripps Howard News Service and the Wall Street Journal, and appears on the Fox News Channel. Michael Rubin, visiting scholar at AEI, writes for the New Republic (controlled by staunchly pro-Israel Martin Peretz), the New York Times, and the Daily Telegraph. Reuel Marc Gerecht, a resident fellow at the AEI and director of the Middle East Initiative at the Project for a New American Century [a neocon group], writes for the Weekly Standard and the New York Times. Another prominent AEI member is David Wurmser who formerly headed the Middle East Studies Program at the AEI until assuming a major role in providing intelligence disinformation in the lead up to the war in Iraq. His position at the AEI was funded by Irving Moscowitz, a wealthy supporter of the settler movement in Israel and neocon activism in the US.[2] At the AEI Wurmser wrote op-ed pieces for the Washington Times, the Weekly Standard, and the Wall Street Journal. His book, Tyranny’s Ally: America’s Failure to Defeat Saddam Hussein, advocated that the United States should use military force to achieve regime change in Iraq. The book was published by the AEI in 1999 with a Foreword by Richard Perle.

Given this history—and understanding the Sacklers’ modus operandi—I should not have been surprised that AEI has been involved in promoting false, Purdue-funded research that doubtless had a prominent role in creating the crisis. Here’s Tucker’s segment:

@TuckerCarlson links Purdue Pharma's opioid epidemic to the American Enterprise Institute, a neocon outfit. No surprise really. An excellent example of the corruption of Conservatism Inc. https://t.co/Z9LPSDA9zi

— Kevin MacDonald (@TOOEdit) December 6, 2019

In my 2017 article I described how Purdue funded research that found that Oxycontin was not significantly addictive.

Purdue essentially created a very large community of people who benefited financially from prescribing opioids. They set up and funded organizations that lobbied for more aggressive treatment of pain by treatment with opioids. Millions were funneled into organizations like the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine and Purdue’s own advocacy group, Partners Against Pain, as well as to medical professionals willing to provide data supporting the movement. Purdue hired an army of sales reps to promote opioids to all medical personnel, from doctors to physician assistants. A consistent part of the pitch was to minimize addiction rates. Purdue claimed addiction rates were less than 1% by cherry picking studies that did not examine the effects of long-term use. Other studies often showed much higher rates, as high as 50%. This misrepresentation was at the root of the $600M judgement against Purdue obtained by the US government.

The AEI could have been included in this assessment It received $50,000/year from Purdue from 2003 “until recently”—~$800,000 total—pocket change for a family that walked away with at least $11 billion. The original “research” touting the non-addictive properties of Oxycontin and based on 38 subjects was performed by R. K. Portnoy of the Metropolitan Jewish Health System. But there were others:

Scott Fishman and Perry Fine [were] prominently associated with the American Pain Foundation which got 88% of its budget from Purdue and other pharmaceutical companies. Fine has been funded by at least a dozen drug companies and Fishman has had relationships with at least eight companies, including Purdue, for which he was a consultant, paid speaker and recipient of research support. They claim that all this financial remuneration did not affect their opinions. And if you believe that, you are an idiot.

As Tucker notes, in 2004 the New York Times published an article by AEI writer Sally Satel, presumably Jewish, opposing jail sentences for doctors who over-prescribed opioids after running it past a Purdue lobbyist. And in 2007 the Wall Street Journal, a major neocon media outlet, published another article by Satel in which she called Oxycontin a “godsend” and lamented that it not being prescribed enough.

Satel is intimately associated with the AEI as a Resident Fellow. She is typical of our new elite and its involvement in elite institutions and media. Wiki:

Sally L. Satel(born January 9, 1956) is an American psychiatrist based in Washington, D.C. She is a lecturer at Yale University School of Medicine, the W.H. Brady Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and author.

She has continued writing on the topic with, e.g., an article in Politico from 2018 in which she argues that physician-prescribed opiates are not the problem:

I have studied multiple surveys and reviews of the data, which show that only a minority of people who are prescribed opioids for pain become addicted to them, and those who do become addicted and who die from painkiller overdoses tend to obtain these medications from sources other than their own physicians.

The two studies linked above do not actually support her conclusions. There is no reason to trust any of the conclusions of the first study. It reviewed 17 studies with “extremely heterogeneous results”—not surprising given that “all the present data derived from studies with weak designs, e.g. uncontrolled case series and cross-sectional surveys. These studies suffer from low-quality reporting, with little information on the characteristics of patients, type of opioids administered and route of administration.” One wonders how many of the studies were funded by drug companies like Purdue. This review only used studies with patients with chronic pain in supervised settings, and did not address opioid prescription in the public at large, especially for non-chronic pain. Recall that the entire focus of Purdue’s propaganda was to prescribe Oxycontin for non-chronic pain in order to widen the use of the drug. The previous practice of prescribing opioids only for serious chronic pain was labeled cruel. Hospitals were pressured to administer opioids for fear that they would have lower rankings after Purdue provided data to regulatory agencies, resulting in a “dramatic increase” in prescriptions. Moreover, neither study cited by Satel addressed the issue of people who had been prescribed opioids going to the black market for drugs like heroin after treatment.

The second concluded, contrary to her assertions, notes that

The extended prescription of opioids (>8 weeks) for the treatment of chronic pain has questionable benefits for individual patients and presents substantial public health risks. The risks of overdose and addiction from this prescribing practice — both among patients with chronic pain and the public at large — increase with higher doses (>100 MME), longer duration of prescribing, and perhaps the use of long-acting opioids. Despite these facts, a Medicaid study showed that more than 50% of opioid prescriptions were for doses higher than 90 MME and for periods of more than 6 months. Better results can be obtained by using the most contemporary guidelines for pain management.

Contemporary guidelines are much more restrictive, really a return to previous practice before Purdue began its promotional campaign. Other studies are quite clear that “Misuse or abuse of prescription drugs, including opioid-analgesic pain relievers, is responsible for much of the recent increase in drug-poisoning deaths” (here).

The entire episode is an excellent example of how our new elite works. I concluded in my paper on the opioid disaster:

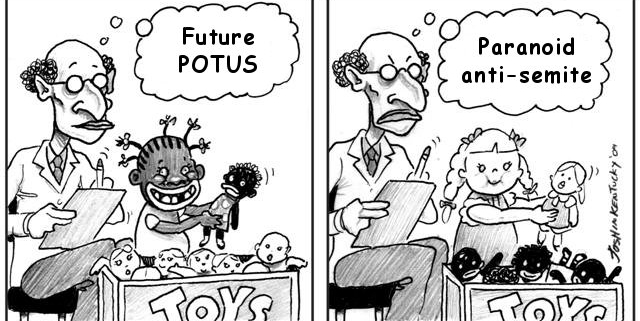

The opioid phenomenon reflects aspects of Jewish activism in general. These are top-down movements that are well-funded, they have access to the most prestigious institutions of the society, and, because of this prestige, they are able to propagate fake science. In the case of the Jewish drive to enact the 1965 immigration law, pro-immigration committees were funded, fraudulent academic studies were created on the benefits of immigration, prominent people were recruited (like JFK, recruited to put his name on a book titled A Nation of Immigrants written by Myer Feldman and published by the ADL), positive articles about immigration appeared in the media, lobbyists and politicians were paid. The main fake scientists discussed in The Culture of Critique were the Boasians with their fake race science (utilized in the debates over the immigration law of 1965), psychoanalysis with its fake sex science, and the Frankfurt School with its fake theory that ethnocentric Whites have a psychiatric disorder resulting from poor parenting. Like the fake scientists who participated in promoting the opioid epidemic, these activists had access to prestigious academic institutions and, in the case of the Frankfurt School and other activist academic research in the 1950s and 1960s, their research was funded by the organized Jewish community, such as the American Jewish Committee, and promoted by Jewish academics.

Or consider the neoconservative infrastructure, with think tanks funded, prominent spokesmen at prestigious universities, and a very large media presence. Neocons can bet that if they are forced out of a job in the Departments of State or Defense that they will have many options to fall back on. Despite promoting disastrous policies, such as the war in Iraq, and despite their obvious ethnic loyalties to Israel, they are still a very powerful component of the U.S. foreign policy establishment.

Jews are an incredibly successful and influential group. We can’t win unless we understand that.

In my 2004 article I included AEI as part of the neoconservative infrastructure of our new elite. Now we know that the AEI—an exemplar of Conservatism Inc.—is deeply involved in the greatest public health crisis of our time. As many have noted, Conservatism Inc. has utterly failed to conserve anything of importance. The AEI, along with the mainstream Jewish community, favors the immigration tsunami which is displacing the traditional White majority of America. For example, I notice that an AEI writer, James Pethokoukis, takes seriously Bryan Caplan’s proposal for open borders, giving Caplan softball questions and never raising the interests of White America. Could there be a greater indictment of Conservatism Inc.?

States’ attorneys general and many other jurisdictions are suing not only Purdue Pharma, but also individual Sackler family members. The outcome, however, remains in doubt. The most recent development (November 6) is that a federal judge, Robert Drain of the Southern District of New York, has extended protection from lawsuits against Purdue. An issue was whether Richard Sackler himself was liable. The answer, of course, is a resounding yes, although his attorney claims that “was not involved in the marketing of opioid OxyContin.”

Sackler was a key figure in the development of Oxycontin being the moving force behind Purdue Pharma’s research around 1990 that pushed Oxycontin to replace MS contin that was about to have generic competition. Sackler also worked to enlist Russell Portenoy and J. David Haddox into working within the medical community to push a new narrative claiming that opioids were not highly addictive. In pushing Oxycontin through to FDA approval in 1995 Sackler managed to get the FDA to approve a claim that Oxycontin was less addictive than other pain killers, although no studies on how addictive it was or how likely it was to be abused had been conducted as part of the approval process. The addictive nature of opiates had been known for thousands of years.

Sackler became president in 1999. In 2001 he issued an email to employees of the company urging them to push a narrative that addiction to Oxycontin was caused by the “criminal” addicts who had the addiction, and not caused by anything in the drug itself. Sackler also urged pharmaceutical representatives to urge doctors to prescribe as high doses as possible to increase the company profits.

He was made co-chairman in 2003. Sackler was in charge of the research department that developed OxyContin. As president, he approved the targeted marketing schemes to promote sales of OxyContin to doctors, pharmacists, nurses, academics, and others. Shelby Sherman, an ex-Purdue sales rep, has called these marketing schemes “graft”.

In 2008, Sackler, with the apparent knowledge of Mortimer Sackler and Jonathan Sackler, made Purdue Pharma measure its “performance” in proportion to not only the number but also the strength of the doses it sold, despite allegedly knowing that sustained high doses of OxyContin risked serious side effects, including addiction. (Wiki)

The judicial system is a central part of our corrupt new elite, so I’ll be very surprised if any of the Sackler family give up much of their ill-gotten gains—much less spend the rest of their lives in prison. Even life in prison, the best that could possibly be hoped for, is far too lenient for a family that is ultimately responsible for over 200,000 deaths.