Jewish Scientist Who Developed New Vaccine “Saved the World”

Dr. Drew Weissman (along with colleague Katalin Kariko) at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine has been lauded as “Penn Professor (who) ‘Saves the World’ with COVID Vaccine Research.” (Kariko is excluded from the headline in this Jewish Exponent article.) Weissman and Kariko have been lavishly celebrated for their “breakthrough” with mRNA technology. “Earlier this year, Brandeis University and the Rosenstiel Foundation honored the scientists with the Lewis S. Rosenstiel Award for Distinguished Work in Basic Medical Research.”

What I am about to relate is an interlocking nexus of Jewish wealth, big pharma, and connections to the academic community. This goes back a long way.

Brandeis University “was named for Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1856–1941), the first Jewish justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.” We saw Brandeis in the essay “Jewish Control of U.S. Presidents #1: Woodrow Wilson.” Brandeis was installed as the first Jewish justice of the Supreme Court as part of a deal Wilson made with Samuel Untermeyer, Jewish attorney and Wilson handler through blackmail and bribery. Under “Our Jewish Roots,” Brandeis U states: “At its core, Brandeis is animated by a set of values that are rooted in Jewish history and experience.” It espouses “the Jewish ideal of making the world a better place through one’s actions and talents.” This is reminiscent of the “Science Tikkun” of aggressive Jewish vaccine promoter Peter Hotez.

Lewis S. Rosenstiel was a Jewish organized crime boss who made his first fortune bootlegging illegal liquor during Prohibition. He went on to run child-raping blackmail operations prior to those of Roy Cohn, Jewish mob attorney in New York, and Jeffrey Epstein’s infamous child-rape operations most recently.

Weissman and Kariko also won a Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences from the Breakthrough Prize Foundation. “In July 2012, Yuri and Julia Milner established the Breakthrough Prize, joined the following year by Sergey Brin, Priscilla Chan, Anne Wojcicki and Mark Zuckerberg.” Apart from Chan who is Chinese, all are Jews including Milner, a “Soviet-born Israeli entrepreneur“ whose investment firm DST Global (“The Quiet Conqueror”) invests in Facebook, and who personally invested in 23andMe, whose CEO is Anne Wojcicki. Wojcicki was married to Brin, co-founder of Google and president of parent company Alphabet. Anne’s sister Susan Wojcicki was CEO of Youtube, and Zuckerberg is of course co-founder of the Facebook internet social media platform.

The Perelman Family’s-Funded Medical School—and Much Else

While the interrelationships among so many Jews overseeing the most powerful internet and data companies in the world are noteworthy, here our focus is on Jewish interrelationships in the medical industry. For an analysis of the Jewish role in creating today’s modern pharmaceutical-based medical system, see “The Jewish Origins of the For-Profit Medical Industry.”

Other high-level Jewish crime lords besides Brandeis and Rosenstiel are also funding medical research and development, as discussed in Covert Covid Culprits (review here):

Jewish organized crime oligarch and child-raping blackmail ringleader Leslie Wexner [Epstein’s boss] founded and is funding the Wexner School of Medicine. By November 2020, the Wexner School conducted AstraZeneca covid vaccine trials, on up to 500 victims, with follow-up evaluations for two years.[1]

Jewish organized crime oligarch and child-raping blackmail ringleader Leslie Wexner [Jeffrey Epstein’s boss] founded and is funding the Wexner School of Medicine. By November 2020, the Wexner School conducted AstraZeneca covid vaccine trials, on up to 500 victims, with follow-up evaluations for two years.[1]

More relevant to Weissman, Jewish billionaire oligarch and financial schemer Ronald Perelman (“once touted as America’s richest man.”) is the son of the couple who in 2011 provided the immense grant that gives the Perelman School, where Weissman works, its name. In “Raymond and Ruth Perelman Donate $225 Million to the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine,” the subtitle reads, “Largest Single Naming Gift To A School Of Medicine In U.S. History.” Raymond Perleman’s (deceased) Wikipedia entry says “He was Jewish.”

Perelman’s entry states: “He was raised in a Jewish family… and is the grandson of Litvak (Jewish Lithuanian) immigrants.” In a Forbes (not to be confused with Perelman’s holding company MacAndrews and Forbes) article titled “Don’t Mess With Me,” we learn that “he is an observant Jew who doesn’t work from sundown Friday to Sunday morning and who, as the Talmud demands, on Saturdays always prays in a group of ten Jewish men, no matter where he is in the world.”

The Forbes article calls Perelman “one of America’s most feared corporate raiders” and a “giddily competitive, 5-foot-7 corporate barbarian.” Also, “Ronald Perelman is a multi-billionaire Jew with a trail of corruption and dirty dealing—what his Wikipedia entry calls ‘controversy.’”[2] Perelman’s name is found in Epstein’s notorious black book on page 43: “…many of these ‘raiders,’ specifically Ron Perelman… dined with Epstein at Epstein’s home throughout the 2000s and whose political fundraiser for Bill Clinton’s re-election campaign was attended by Epstein in the mid-90s…”[3] “Perelman would later be listed as a frequent dinner guest of Epstein’s.”[4]

Ron Perelman… is a veteran of the infamous corporate raiders of Drexel Burnham Lambert during the 1980s. … Perelman’s business tactics were known to be informed by his volcanic temper and his ruthlessness, with former Salomon Brothers CEO John Gutfruend once having remarked that “believing Mr. Perelman has no hostile intentions is like believing the tooth fairy exists.”[5]

The Perelman School of Medicine has over 2,600 full-time faculty members, 781 medical students, more than 1,400 residents and fellows, 967 PhD students, 218 MD-PhD students, 782 post-doctoral fellows, and over 6,800 Perelman School of Medicine employees.

U Penn’s Jewish President

President of the University of Pennsylvania, within which is the Perelman School, was Amy Gutmann, serving from 2004 to 2020 when she resigned to accept the appointment as U.S. Ambassador to Germany. This made her “the longest-serving president in the history of the University of Pennsylvania.” In a Princeton Magazine profile (she was formerly the first Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor at Princeton, founding director of its University Center for Human Values, and provost), Gutmann stated:

My father, Kurt, was the youngest of five children in an Orthodox Jewish family living near Nuremberg when Hitler came to power. At a remarkably early age, under incredibly trying conditions, he had the wisdom, foresight and courage to act on the deeply troubling developments and decided to escape. His brave decision profoundly shaped my life and that of my family. I would not be here today had he acted differently.

We are to understand that Amy is another holocaust survivor, because her father was. It is both apropos and an insult that our U.S. Ambassador to Germany today is the Jewish daughter of an alleged holocaust survivor.

Gutmann is co-author of Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race, and is described as an “eminent moral and political philosopher.” The publisher’s description states:

Gutmann examines alternative political responses to racial injustice. She argues that American politics cannot be fair to all citizens by being color blind because American society is not color blind. Fairness, not color blindness, is a fundamental principle of justice. Whether policies should be color-conscious, class conscious, or both in particular situations, depends on an open-minded assessment of their fairness. Exploring timely issues of university admissions, corporate hiring, and political representation, Gutmann develops a moral perspective that supports a commitment to constitutional democracy.

Hers is a distinctly Jewish perception of racial justice and “fairness” (i.e., equity whereby all groups achieve the same regardless of talents and abilities in an attempt to raise up Black and Latino socioeconomic profiles). Co-author K. Anthony Appiah “draws on the scholarly consensus that ‘race’ has no legitimate biological basis.”

Immediately as U Penn president, Gutmann launched the Penn Compact, which went on “to integrate knowledge across academic disciplines with a strong emphasis on innovation: Penn was named No. 4 in Reuters’ Top 100 World Innovative Universities in 2017.” This entry lists as “Notable Alumni” Ronald Perelman and Donald Trump. It also shows the number of patents which U Penn has been granted (170), with a commercial impact over 50% above the average. This brings us to the profit motive of Dr. Weissman’s current research.

The New Vaccines: Follow the Money

Weissman

studied biochemistry and enzymology at Brandeis University and earned an MD/PhD in immunology and microbiology from Boston University in 1987. After a residency in Boston, he pursued a fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, where he worked closely with Anthony Fauci (Hon.’18), now director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, whom (Weissman) describes as “one of the great drivers of my research interest.” [Fauci retired at the end of 2022 — KH]

The above quote is from “How Scientists Drew Weissman… and Katalin Karikó Developed the Revolutionary mRNA Technology inside COVID Vaccines.”

Anthony Fauci as director of NIAID became notorious throughout the promotion of the covid-19 pandemic for his advocacy of the new mRNA vaccines—and no other possible natural health measure or intervention, except masks. We must consider that Fauci may also have directed Weissman in his “research interest,” leading to the immensely profitable covid vaccines.

In February Pfizer announced its 2022 sales of covid vaccines plus its new oral paxlovid covid drug totaled $56 billion, with total profits at $31.4 billion. Moderna’s only commercial product was its covid vaccine, and its gross sales in 2022 were $18.2 billion.

News had emerged announcing that Weissman is pursuing the next fabulously lucrative vaccine product, a “universal vaccine.” ABC’s “Philadelphia scientists on quest to develop universal coronavirus vaccine” which was published in February 2022, quotes Weissman:

There have been three epidemics with coronavirus in the past 20 years. The problem with chasing variants is by the time you’ve made a vaccine the variant is gone and a new variant appears. …

We have two vaccines that work well. We’re making more because, in the end, we might have to mix vaccines together to get the protection possible.

We see how the theory of constantly emerging “variants” (they used to be called “mutations”) provides job security for Weissman, and guarantees ongoing profits for pharmaceutical vaccine makers.

Covid Vaccine Damage

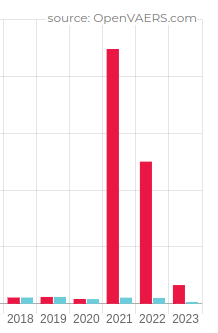

Even without mixing mRNA vaccines, the damage from a single mRNA vaccine (as a result of the many doses needed) has been staggering. The U.S. government’s own Vaccine Adverse Reporting System (VAERS) provides the numbers as of May 5:

- 35,324 COVID Vaccine Reported Deaths

- 199,790 Total COVID Vaccine Reported Hospitalizations

- 1,556,050 COVID Vaccine Adverse Event Reports

Here the blue bars represent deaths from non-COVID vaccines, leaving the red bars for COVID vaccine deaths. Note that “occasional” reports come from outside the U.S.

Recall that “the Lazarus study… showed that less than 1% of events are reported to VAERS”[6] This study was concluded in 2010, and government health agencies have done nothing since to improve vaccine adverse event reporting, while doing much to improve vaccine promotion.

Pfizer’s own vaccine damage data was released through a Freedom of Information Act request. It covers the three-month period from 1/12/2020 – 2/28/2021, the very beginning of its covid vaccine deployment. Almost 159,000 events were reported world-wide, the largest number being from the U.S. (almost 35,000). Among these were over 1,200 deaths. In pregnant mothers, 29 out of 270 pregnancies resulted in spontaneous abortion or neo-natal death (p. 12). That is almost 11%. Russian roulette is 17%. For pregnant mothers to accept the covid vaccine would be like playing Russian roulette with their babies’ lives with a 9-chamber revolver. Pfizer was expecting to continue this “pharmacovigilance” program for two years (but don’t expect any of the data to become public), but these reports of death and damage accrued in only the first three months.

New Vaccines at ‘Breathtaking Speed’

Weissman is not deterred by huge spikes in death and damage from the first mRNA vaccines. The Bostonia (Boston University’s Alumni Magazine) article continues:

[Weissman and Kariko] pioneered the mRNA technology that is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of vaccine development and the future of gene therapies. Not only have the new mRNA vaccines proven to be more effective and safer [!] than traditional vaccines, they can be developed and reengineered to take on emerging pathogens and new variants with breathtaking speed [i.e., Warp Speed-KH]. Using mRNA technology, Pfizer-BioNTech designed its coronavirus vaccine in a matter of hours.

Operation Warp Speed was President Trump’s program to fast-track covid vaccines. It was a public-private partnership including the Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. military. It had a budget of $10 billion and granted $6 billion of that to pharmaceutical companies and other vaccine development firms. OWS used a private company, Advanced Technology International, to award the grants, in order to “bypass the regulatory oversight and transparency of traditional federal contracting mechanisms.”

Weissman’s technology is all about speed, something highly dangerous when applied to vaccine testing and safety.

There were “enormous possibilities,” Weissman says. The scientists believed their technology had the potential to transform medicine, opening the door to countless new vaccines, therapeutic proteins, and gene therapies.

And money, as we have seen.

[Weissman and Kariko’s] discovery caught the attention of two biotech newcomers, Moderna of Cambridge, Mass., and Germany’s BioNTech. Both companies eventually licensed Weissman and Karikó’s patents. (Karikó was hired by BioNTech in 2013, and the company would later partner with US pharmaceutical giant Pfizer on vaccine development. The two companies also now support Weissman’s lab.)

His frustration with how the United States is managing the pandemic has led him to focus on vaccine access for the rest of the world. Weissman is currently working with the governments of Thailand, Malaysia, South Africa, and Rwanda, among others, to develop and test lower-cost COVID vaccines.

‘Immunize the World’

The Bostonia article provides the same Weissman quote as the ABC article, but goes further:

There have been three coronavirus epidemics in the past 20 years,” he explains. “You have to assume there are going to be more. We’re now working on a vaccine that will protect against every variant that will likely appear. Our thinking is that we’ll use it as a way to immunize the world—and prevent the next pandemic from happening in the future.

MERS-CoV, another supposed coronavirus, was said to be spreading from camels to humans primarily in the Middle East. The case fatality rate was said to have been 30-35%, although as with SARV-Cov-2, “Most patients who have died had underlying comorbidities and developed pneumonia or renal failure.” Again, it was health care settings that most caused the symptoms. “45% were healthcare-associated infection.” Some “infections’ were recognized as “asymptomatic.” Though the disease was predicted to possibly spread to the U.S., “no sustained transmission had been reported by late 2014,” and the CDC reported only 2 possible cases. Though no vaccine has been developed, as of 2019 development prospects continue using six different technologies, including DNA and nano-particle vaccines. Profit prospects look promising.

When Weissman says we have had three coronavirus epidemics, and we have to assume we are going to have more, we should believe him. The past three have proven their effectiveness at controlling population behavior and generating pharmaceutical company profits, as well as research funding for Weissman’s efforts to “immunize the world.” .

‘Charging Forward on a Mind-bending Spectrum of Applications’ – “It’s Limitless”

But Weissman is hardly stopping with coronaviruses. He’s working on about 20 other vaccines for diseases from malaria to HIV, with several moving into clinical trials. His lab is also exploring new gene therapies to treat immune deficiencies like cystic fibrosis and genetic liver diseases.

Meanwhile, biotech companies like Moderna and BioNTech are charging forward on a mind-bending spectrum of mRNA applications, including personalized cancer vaccines and autoimmune therapies: “as he looks to the future, he sounds genuinely awed by the staggering potential of the technology he and Karikó invented: ‘It really is exciting. It’s limitless.’”

It appears Weissman’s personal fortunes were only relatively improved by his twenty years of research and development of modified mRNA technology. The patenting of the technology was a complex matter. Basically the patents belong to U Penn and licensing sold to private firms and individuals. Kariko became an executive at BioNTech, and received $2 million two separate times in licensing deals.

As for Dr. Drew Weissman, MIT Technology Review reported in early 2021:

There are fantastic fortunes to be made in mRNA technology. At least five people connected to Moderna and BioNTech are now billionaires… Weissman is not one of them, though he stands to get patent royalties. He says he prefers academia, where people are less likely to tell him what to research—or, just as important, what not to. He’s always looking for the next great scientific challenge: “It’s not that the vaccine is old news, but it was obvious they were going to work.” Messenger RNA, he says, “has an incredible future.”

In-credible is the word. As we’ve seen, Dr. Anthony Fauci as director of NIAID told Weissman what to research, and his research has reaped enormous profits and stands to reap much more. This financial abundance has come at the cost of more lives than any previous vaccine by far. The death and damage signals in the VAERS and Pfizer’s own “pharmacovigilance” data are being ignored. By no means was it “obvious” the vaccines “were going to work.” No previous attempt at marketing a coronavirus vaccine had succeeded; the modified mRNA technology Weissman offered had been tried but never been used in any vaccine before, and an objective view of the covid vaccine clinical trials showed it was a failure.

Weissman is moving forward boldly with more modified mRNA medical technology, and no doubt more patent royalties. His Jewish nature and his Jewish network compel him.

[1]Haemers, Karl, Covert Covid Culprits: An Inquest Chronicle, USA, p. 245

[2]Ibid, p. 98

[3]Webb, Whitney, One Nation Under Blackmail, Vol. 2, Trine Day, Walterville OR, 2022, p. 8

[4]Ibid, p. 216

[5]Ibid, p. 215

[6]Haemers, p. 184

Kriss Donald and Mary-Ann Leneghan, two young white victims of Clown World

Kriss Donald and Mary-Ann Leneghan, two young white victims of Clown World