Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism, and the Decline of Western Art, Part 3 of 3

Convergence by Jackson Pollock (1952)

Abstract Expressionism and the Culture of Critique

Abstract Expressionism was disproportionately a Jewish cultural phenomenon. It was a movement populated by legions of Jewish artists, intellectuals, critics, and patrons. Prominent gentile artists within the movement like Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell married Jewish women (Lee Krasner and Helen Frankenthaler). Willem de Kooning defied the trend — though had to ingratiate himself with the Jewish intellectual and cultural elite focused around the journal Partisan Review which was “dominated by editors and contributors with a Jewish ethnic identity and a deep alienation from American cultural and political institutions.”[i]

For Jewish writer Alain Rogier, it seems “hardly a coincidence that Jews made up a large percentage of the leading Abstract Expressionists.” It was an art movement where the culture of critique of Jewish artists, frustrated that the post-war American prosperity prevented the coming of international socialism, turned inward and instead “proposed individualistic modes of liberation.” This mirrored the ideological shift that occurred among the New York Intellectuals generally who had “gradually evolved away from advocacy of socialist revolution toward a shared commitment to anti-nationalism and cosmopolitanism (i.e. the multicultural project), ‘a broad and inclusive culture’ in which cultural differences were esteemed.”[ii] Doss notes how this ideological shift manifested itself among the artists who became the Abstract Expressionists:

As full employment returned, New Deal programs were terminated — including federal support for the arts — the reformist spirit that had flourished in the 1930s dissipated. Corporate liberalism triumphed: together, big government and big business forged a planned economy and engineered a new social contract based on free market expansion. … With New Deal dreams of reform in ruins, and the better “tomorrow” prophesied at the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair having seemingly led only to the carnage of World War II, it is not surprising that post-war artists largely abandoned the art styles and political cultures associated with the Great Depression.[iii]

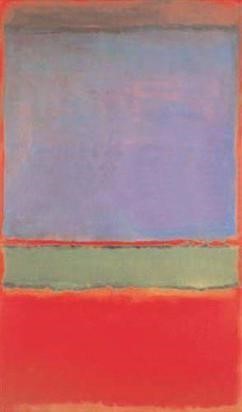

The avant-garde artists of the New York School instead embraced an “inherently ambiguous and unresolved, an open-ended modern art… which encouraged liberation through personal, autonomous acts of expression.” The works of the Abstract Expressionists were “revolutionary attempts” to liberate the larger American culture “from the alienating conformity and pathological fears [especially of communism] that permeated the post-war era.”[iv] Rothko claimed that “after the Holocaust and the Atom Bomb you couldn’t paint figures without mutilating them.” His friend and fellow artist Adolph Gottlieb, declared that: “Today when our aspirations have been reduced to a desperate attempt to escape from evil, and times are out of joint, our obsessive, subterranean and pictographic images are the expression of the neurosis which is our reality. To my mind… abstraction is not abstraction at all… it is the realism of our time.”[v]

At the heart of Abstract Expressionism lay a vision of the artist as alienated from mainstream society, a figure morally compelled to create a new type of art which might confront an irrational, absurd world—a mentality completely in accord with that of the alienated Jewish artists and intellectuals at the heart of the movement who viewed the White Christian society around them with hostility. MacDonald notes that the New York Intellectuals “conceived themselves as alienated, marginalised figures — a modern version of traditional Jewish separateness and alienation from gentile culture. … Indeed [Norman] Podhoretz was asked by a New Yorker editor in the 1950s “whether there was a special typewriter at Partisan Review with the word ‘alienation’ on a single key.”[vi]

During the 1950s Jewish artists and intellectuals chafed against the social controls enforced by political conservatives and religious and cultural traditionalists who limited Jewish influence on the culture, “much to the chagrin of the Frankfurt School and the New York Intellectuals who prided themselves in their alienation from that very culture.” This all ended, together with Abstract Expressionism as an art movement embodying the alienation of the New York Intellectuals, with the triumph of the culture of critique in the 1960s, when radical Jews and their gentile allies usurped the old WASP establishment, and thus “had far less reason to engage in the types of cultural criticism so apparent in the writings of the Frankfurt School and the New York Intellectuals. Hollywood and the rest of the American media were unleashed.”[vii]

Jews and Modernism

In his exposition of the political significance of the widespread Jewish involvement in cultural modernism the Jewish historian Norman Cantor noted that: “Something more profound and structural was involved in the Jewish role in the modernist revolution than this sociological phenomenon of the supersession of marginality. There was an ideological drive at work.”[viii] This ideological drive was the urge to subject Western civilization (deemed a “soft authoritarianism” fundamentally hostile to Jews) to intensive and unrelenting criticism — in the process of which they spawned a massive literature of cultural subversion throughout the post-war period.

Kevin MacDonald notes how there was a great deal of influence and cross-fertilisation between the New York Intellectuals and the Frankfurt School. Both promoted modernism in art at least partly because of its apparent compatibility with expressive individualism, but also because it was seen as being capable of alienating people from Western capitalistic societies. For Frankfurt School intellectual Walter Benjamin the purpose of modern art was to spread the kind of cultural pessimism that would bring on the revolution, insisting that “To organise pessimism means nothing other than to expel the moral metaphor from politics.” His colleague, Willi Munzenberg, saw the central role of the Frankfurt School as being “to organise the intellectuals and use them to make Western Civilisation stink. Only then, after they have corrupted all its values and made life impossible, can we impose the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

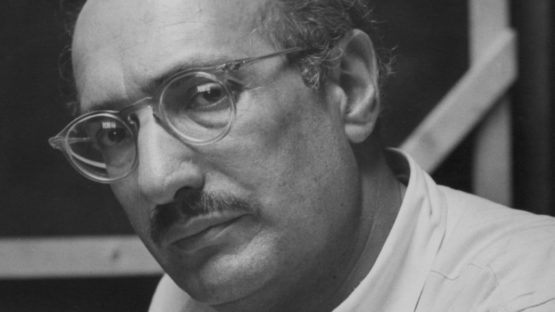

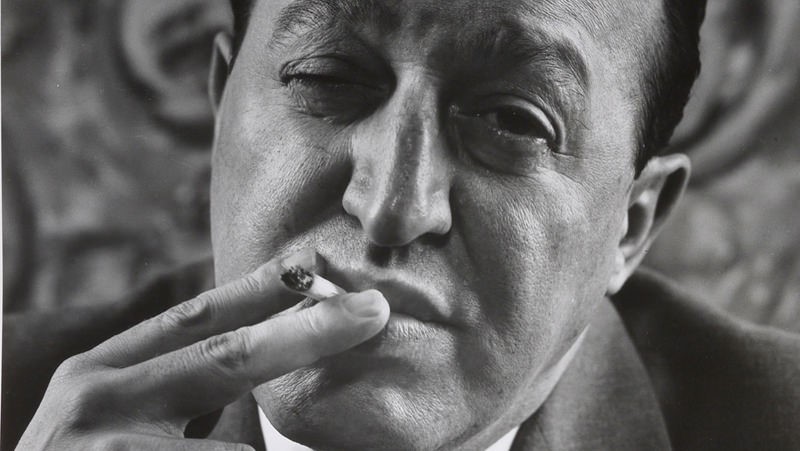

Clement Greenberg and the New “American” Art

Clement Greenberg was the most influential theorizer and promoter of modernism in America during the middle years of the twentieth century. His advocacy helped to bring about the institutionalisation of Abstract Expressionism and to secure the dominance of American modernist art in the immediate post-war period. MacDonald notes that Greenberg “made his reputation entirely within what one might term a Jewish intellectual milieu” including as “a writer for PR, managing editor of Contemporary Jewish Record (the forerunner of Commentary), long-time editor of Commentary under Elliot Cohen, as well as art critic for The Nation.”[ix] Greenberg’s Jewish identity was strong, and he once avowed that “that the quality of Jewishness is present in every word I write, as it is in almost every word of every other contemporary Jewish writer.”[x] He also claimed that it likely “that by world historical standards the European Jew represents a higher type than any yet achieved in history.”[xi]

Clement Greenberg

Greenberg’s later rejection of Pop and Conceptual Art led to a period when his writings and preferences were dismissed by those who aligned themselves with the views of rival Jewish art guru Harold Rosenberg. This arose from Greenberg’s dogmatic advocacy of abstraction, and his distaste for commercial popular culture — what he called “kitsch” in his most famous essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) — his response to the destruction and repression of modernist art in National Socialist Germany and the Soviet Union. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” one of the most influential essays of the twentieth century, made Greenberg’s name as a critic and led to his participation in the world of cultural journalism as an editor of Partisan Review.

It is not hard to detect an underlying concern with anti-Semitism in Greenberg’s famous essay. There was a general understanding among both the Frankfurt School and the New York Intellectuals that mass culture — whether in the Soviet Union (both groups were anti-Stalinist), National Socialist Germany, or bourgeois United States — promoted conformism and escape from harsh political realities. It “offered false pleasure, reaffirmed the status quo, and promoted a pervasive conformity that stripped the masses of their individuality and subjectivity.”[xii] By contrast, avant-garde art had the potential to foster the kind of subjective individualism that could disconnect the masses from their traditional familial, religious and ethnic bonds — thereby reducing the salience of Jews as an outgroup and weakening the anti-Semitic status quo within these societies.

In his essay, Greenberg downplays the culturally critical potential of avant-garde art, and instead seeks to account for the ubiquity of “kitsch” in totalitarian societies by stressing its usefulness in ingratiating a regime with the masses — a practice that, he informs us, will only cease when these regimes “surrender to international socialism.” He writes:

Where today a political regime establishes an official cultural policy, it is for the sake of demagogy. If kitsch is the official tendency of culture in Germany, Italy and Russia, it is not because their respective governments are controlled by philistines, but because kitsch is the culture of the masses in these countries, as it is everywhere else. The encouragement of kitsch is merely another of the inexpensive ways in which totalitarian regimes seek to ingratiate themselves with their subjects. Since these regimes cannot raise the cultural level of the masses — even if they wanted to — by anything short of a surrender to international socialism, they will flatter the masses by bringing all culture down to their level. It is for this reason that the avant-garde is outlawed. … Kitsch keeps a dictator in closer contact with the “soul” of the people. Should the official culture be one superior to the general mass-level, there would be a danger of isolation.[xiii]

Greenberg’s thesis is not without validity. Indeed one of the striking features of modern Western life under Jewish cultural hegemony has been an all-pervasive popular culture of Hollywood that is supersaturated with the rankest multi-cultural and multi-racial kitsch. Despite the real-world failure of the utopian vision being relentlessly endorsed, this form of easily assimilated kitsch (seasoned with liberal doses of sex, violence and schmaltz) works very well to brainwash the great bulk of White people and avert even the mildest forms of rebellion.

Greenberg’s famous essay in Partisan Review

“Kitsch” works for the Jews of Hollywood for the same reason it worked for Hitler and Stalin. This is because kitsch is defined by efficiency of communication, while the avant-garde alienates some viewers “simply because this was an inescapable by-product of their formal experiments and of their rejection of kitsch.”[xiv] Barlow notes that, for Greenberg:

Kitsch worked to maximize effect, while the avant-garde sought to address cause. Both commerce and totalitarian regimes sought maximum penetration of controllable information. They required the culture of kitsch. Mass culture will almost inevitably be kitsch, as passive consumers will comprehend accessible effects more readily than the self-conscious explorations of cause. Only in a truly socialist society will mass culture transcend the psychology of passive consumption. Despite important differences between the two men, Greenberg’s attitude to popular culture is close to that of Theodor W. Adorno.[xv]

Like Greenberg, Adorno initially directed his attack not against the high culture of Western civilization, but against the “mass culture” which warred with it — a “secondary emanation of authority” which was an inescapable product of capitalism. For Adorno, nothing was more abhorrent in the mass culture of America than its music. For him, popular music, riddled with cliché and kitsch, was not art but ideology that promotes a false consciousness that numbs the revolutionary senses of the working class. It is the owners of the means of communication (the capitalist class) that is sovereign in this debased musical culture. Under socialism, Adorno implied, this false consciousness would be swept away and the emancipated proletariat would be whistling the ideology-free music of Schoenberg and Webern in the streets.[xvi] However, as Roger Scruton noted, this aspect of Frankfurt School’s critical theory was later to change fundamentally:

Since the Frankfurters came as exiles to America, there to pour scorn on their hosts, the culture of repudiation has taken another and more home grown form. Instead of focusing on the “mass culture” of the people, it now targets the elite culture of the universities. It is indifferent, or even vaguely laudatory, towards popular art and music, seeing them as legitimate expression of frustration and a challenge to the old forms of highbrow knowledge. Its target is the culture in the sense that I have been defending it: all those artefacts that have stood the test of time, and which are treasured by those who love them for the emotional and moral knowledge that they contain.[xvii]

Unlike his rival Harold Rosenberg, Greenberg never embraced this new critical paradigm. In his essay “Towards a Newer Laocoon” (1940) he articulated his famous claim that resistance to kitsch requires that art “emphasize the medium and its difficulties,” adding that the history of the avant-garde is one of “progressive surrender to the resistance of the medium.”[xviii] Greenberg argued that the vision of the Abstract Expressionists was characterized by a “fresher, opener, more immediate surface,” offensive to standard taste. He related this quality to a “more intimate and habitual acquaintance with isolation,” which was, in his ethnically, morally and culturally particularistic view, “the condition under which the true quality of the age is experienced.”[xix]

Greenberg’s dismissal of Harold Rosenberg’s account of Abstract Expressionism as “action painting” was based on his view that Rosenberg’s claim implied that the active process of painting mattered more than the result — that one chaotic combination of drips and splodges was as good as another. For Greenberg, Rosenberg’s theory gave the green light to charlatans whose work was no more than “stunts.” Such stunts certainly came into prominence with the rise of Pop and Conceptual art during the 1960s as many artists embraced Rosenberg’s claim that the moment of “performance” could itself be art. This aspect of the art scene in the 1960s earned Greenberg’s contempt, but as Barlow points out, “could all too easily be interpreted as the conservative critic whose time had passed — the modern equivalent of Ruskin’s attack on Whistler.”[xx]

Harold Rosenberg

It is somewhat ironic that Greenberg, an ethnocentric Jewish Trotskyite, in his staunch defence of Abstract Expressionism and Post-Painterly Abstraction, and rejection of the “pre-emptive kitsch” of Pop Art, Neo-Dada and Conceptual Art, was pushed into the role of cultural reactionary. The Abstract Expressionists Greenberg championed had been eager to break with the figurative art of the Regionalist painters, but their work (owing to its highly abstract nature) lacked the more overtly ideological form of much of the conceptual art that replaced it. This shouldn’t, however, obscure from us the fact that the rise of Abstract Expressionism coincided with the Jewish takeover of American high culture, and the deposing of the old WASP art establishment. Nor should it obscure the profound influence Greenberg’s ideas continue to have on Western culture.

Since “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” artistic and cultural production in the West has been underpinned by an aggressive “kitschophobia.” Since Greenberg’s essay was published, figurative painting, tonal music, and classical architecture have been regarded with suspicion (if not outright hostility) by cultural elites. It was fear of kitsch that gave rise to the pre-emptive kitsch of postmodern art:

Artists began not to not to shun kitsch but to actively embrace it, in the manner of Andy Warhol, Alan Jones, and Jeff Koons. The worst thing is to be unwittingly guilty of producing kitsch; far better to produce kitsch deliberately, for then it is not kitsch at all but a kind of sophisticated parody. … Pre-emptive kitsch sets quotation marks around actual kitsch, and hopes thereby to save its artistic credentials. … Public galleries and big collections fill with the pre-digested clutter of modern life, brash items of salesmanship which pass their sell-by date the moment they go on permanent display. Art as we knew it required knowledge, competence, discipline and study, all of which were effective reminders of the adult world. Pre-emptive kitsch, by contrast, delights in the tacky, the ready-made, and the cut-out, using forms, colours and images which both legitimize ignorance and also laugh at it, effectively silencing the adult voice. Such art eschews subtlety, allusion and implication, and in the place of imagined ideals in gilded frames it offers real junk in quotation marks.[xxi]

This “kitschophobic” art belligerently shuns the traditional Western preoccupation with beauty—substituting for it a cult of sarcasm, nihilism and ugliness (yet always within a politically correct framework). To be an “authentic” creation, postmodern art must “challenge,” and preferably be offensive, to standard taste. If this requires producing a dead shark in formaldehyde or a crucifix in urine, then so be it. These deliberately ugly and offensive productions, wittingly or unwittingly, provoke among their audiences a disconnection from the traditional reinforcers of ethnocentrism and group cohesion, and engender what Frankfurt School intellectual Georg Lukacs called “a culture of pessimism” reflecting a world “abandoned by God.”

Israel Shamir aptly summarized the process of degeneration that has occurred within Western art over the last 70 years when he noted that: “In the beginning, these were works of some dubious value like the ‘abstract paintings’ of Jackson Pollock. Eventually we came to rotten swine, corrugated iron, and Armani suits. Art was destroyed.” An art that emerged in response to the alienation of Jewish artists and intellectuals in mid-twentieth century America ushered in an art of cultural alienation for everyone. This debasement of the West’s glorious cultural inheritance has sapped the cultural confidence of White people, and contributed to making Western societies, in the eyes of their increasingly atomized populations, increasingly “unlovable” and not worth defending.

[i] MacDonald, Culture of Critique, 211.

[ii] Ibid., 212.

[iii] Erika Doss, Twentieth-Century American Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 124.

[iv] Ibid., 130-1.

[v] Doss, Twentieth-Century American Art, 128.

[vi] MacDonald, Culture of Critique, 212.

[vii] Kevin MacDonald, ‘Review of Thomas Wheatland’s ‘The Frankfurt School in Exile’ Part II’, Occidental Observer, 2009: http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/articles/MacDonald-WheatlandII.html

[viii] Cantor, The Sacred Chain, 303.

[ix] Ibid., 211.

[x] Ibid., 213.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] MacDonald, Review of Thomas Wheatland’s “The Frankfurt School in Exile.”

[xiii] Clement Greenberg,

[xiv] Paul Barlow, In: Key Writers on Art: The Twentieth Century, Ed. By Chris Murray (London: Routledge, 2003), 152.

[xv] Ibid., 150.

[xvi] Roger Scruton, Culture Counts — Faith and Feeling in a World Besieged (New York: Encounter Books, 2007), 70.

[xvii] Ibid., 73.

[xviii] Barlow, Key Writers on Art, 150-1.

[xix] A. Everitt, “Abstract Expressionism” In: Modern Art — Impressionism to Post-Modernism, Ed. By David Britt (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974), 256.

[xx] Barlow, Key Writers on Art, 151.

[xxi][xxi] Roger Scruton, Modern Culture (London: Continuum, 2000), 93.