The Tale of John Kasper

John Kasper

In 2007, I wrote the article on the white activist John Kasper (1929–1998) that will follow these prefatory remarks. I remember it well, because it was the very first writing I did for a personal website I had just set up and still maintain—http://robertsgriffin.com/. I have the sense that this Kasper article has been read by few people over the years, though six months or so after I posted it, a Wikipedia entry on Kasper was created that drew heavily on what I wrote. I felt good about that.

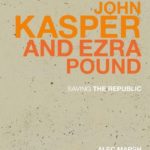

The Kasper writing came to mind this past week (it’s December of 2017) because I happened upon a reference on the internet to a new book about Kasper—John Kasper and Ezra Pound: Saving the Republic (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) by Alec Marsh. I was surprised to see it: I hadn’t imagined that Kasper was a big enough deal to warrant a book about him, but there it was. It isn’t in the university or public library around where I live, and it’s pricey, around $40 for a hardback, $30 for a Kindle. After some soul-searching, I bit the bullet and bought the Kindle. If you decide to get the book, you don’t have to spend that kind of money for it. If a library doesn’t have it in its collection, it can obtain it for you through interlibrary loan. I didn’t want to wait for that process to play out, thus the Visa card payment.

The Kasper writing came to mind this past week (it’s December of 2017) because I happened upon a reference on the internet to a new book about Kasper—John Kasper and Ezra Pound: Saving the Republic (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017) by Alec Marsh. I was surprised to see it: I hadn’t imagined that Kasper was a big enough deal to warrant a book about him, but there it was. It isn’t in the university or public library around where I live, and it’s pricey, around $40 for a hardback, $30 for a Kindle. After some soul-searching, I bit the bullet and bought the Kindle. If you decide to get the book, you don’t have to spend that kind of money for it. If a library doesn’t have it in its collection, it can obtain it for you through interlibrary loan. I didn’t want to wait for that process to play out, thus the Visa card payment.

Author Alec Marsh is an English professor at Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania with a particular interest in Ezra Pound, one of the twentieth century’s preeminent poets and most influential literary personages. Not only did Pound — born in Idaho, lived in Paris, London, Italy, and the U.S., died in Italy — produce great art himself, he inspired and mentored great artists, among them T. S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway. Pound was highly controversial personally, as he was tabbed a fascist and anti-Semite. After reading the Marsh book, it can be said that, for better or worse — most would say worse, I say better — he inspired and mentored young (in his twenties), American, New Jersey childhood, Catholic upbringing, Columbia University, John Kasper.

I respect Marsh’s book very much and recommend it: it’s impressively researched, and it’s even-handed; it’s not a hatchet job on Pound or Kasper as a racist, anti-Semitic nut case, which for many would have been tempting. I didn’t pick up the patronizing and virtue signaling that characterizes so much academic “scholarship” these days. Good for Professor Marsh.

Marsh draws heavily on letters Kasper wrote to Pound which are collected in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University. (Pound’s letters to Kasper didn’t survive).

These letters, often long and informative, sometimes embarrassingly fulsome and worshipful, sometimes gossipy, sometimes mere business transactions revealing records of books (often anti-Semitic tracts) bought by the poet, offer fascinating views of the American Right in the 1950s. Read more

The film Moneyball was well-received by both audiences and critics and an Academy Award contender for best film at the 2012 Oscars. It was based on Michael Lewis’ 2003 nonfiction book by the same name and directed by Bennett Miller from a screenplay written by Aaron Sorkin (who I understand was the guiding force behind the film) and Steven Zaillian. Moneyball recounts the story of the 2002 season of the Oakland A’s major league baseball team. The film centers on A’s general manager Billy Beane’s efforts to put together a winning team that year despite a limited budget. The thesis of this writing is that Moneyball is a good illustration of how the media distort reality and transmit negative perceptions of white people and their ways.

The film Moneyball was well-received by both audiences and critics and an Academy Award contender for best film at the 2012 Oscars. It was based on Michael Lewis’ 2003 nonfiction book by the same name and directed by Bennett Miller from a screenplay written by Aaron Sorkin (who I understand was the guiding force behind the film) and Steven Zaillian. Moneyball recounts the story of the 2002 season of the Oakland A’s major league baseball team. The film centers on A’s general manager Billy Beane’s efforts to put together a winning team that year despite a limited budget. The thesis of this writing is that Moneyball is a good illustration of how the media distort reality and transmit negative perceptions of white people and their ways.